Welcome to the third installation of my journey through the presidency via presidential biographies. Today, we discuss Thomas Jefferson, historically one of the most highly regarded presidents in U.S. History and the author of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s presidency has come under scrutiny in the 21st Century and at various times throughout the nation's history. In some quarters, he is held up as a bastion of freedom, whereas in other quarters, he’s seen much less positively, as a slaver who was an underhanded dealer in the political arena. As far as I’m concerned, it is hard to doubt that Jefferson was highly influential in his time and for maybe 50 years beyond, but I'm not so sure that his influence extends into the present day. To state it bluntly: Jefferson was an 18th Century man and 18th Century thinking doesn’t really hold up in modern day America. More specifically, if his idea of what the federal government should be prevailed to this day, the United States would be a collection of weak individual states, unable to capitalize on its vast collective potential. As president, though, Jefferson acted with a philosophy more in line with Federalist conceptions of what the president should be. To the extent, then that his influence does hold up, it is more in what he did, rather than what he said.

Before I go on, I am coming to the realization that reading one book on each president is, as a project, an interesting way to dip one’s toe into U.S. History. However, I’m finding that it causes me to ask more questions than it answers. In addition, I believe that I have erred by not writing down all of my thoughts before I plowed through eight books. I was reading that fast to accomplish the goal in one year. That’s like taking a road trip through every one of the 48 states in 100 hours. Sure, it can be done, but at the end, what have you accomplished? You’ve sat in a car for 100 hours. For me to expend all this effort and not document my thoughts seems like a waste. What I need to do is to get three or four of these writeups in the can and then plow forward. But here I am on Sunday morning (as I write this), not having done that. Ugh. This next couple of weeks I’m going to try and get all the rest of my completed books written up and then continue the project. I may not get done in one year, but so be it.

Of the eight presidents that I have read about to date, Jefferson is the one that I have revised my opinion downward the most. There are good things about Jefferson, but his actions during the Washington and Adams presidencies were unbelievable in modern light. I think he had middling success as president and his largest accomplishment (admittedly a huge accomplishment) was basically a gift handed to him on a silver platter.

Background

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743 and he died on July 4, 1826, the same day as John Adams. He served as the third president of the United States from March 4, 1801 to March 4, 1809, having won the 1800 and 1804 presidential elections. Jefferson, along with James Madison, were instrumental in founding the Democratic-Republican party and the D-R’s controlled the White House from 1801 though 1829, an astounding run of seven terms (although John Quincy Adams was not too much of a partisan and he was basically a man of No Party). Jefferson’s Vice President during his first term was the infamous Aaron Burr. Burr was replaced in the 1804 election by George Clinton, who served as the fourth Vice President.

Like Adams and Washington before him, Jefferson had an unbelievable career outside of his presidency. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. He served as a diplomat in France, replacing Benjamin Franklin as the Minister to France. He was the first Secretary of State and second Vice President. He is also credited with founding the University of Virginia. Unlike his immediate predecessor Adams, Jefferson’s presidency is considered to be a successful one and he launched a political movement that held power for almost three decades. Part of why Jefferson was successful, in my view, was that he was incredibly lucky to have had the Louisiana Purchase essentially fall into his lap and because as president, he was much more practical (i.e., he abandoned his high falutin’ principles once he held the office) than he was prior to his presidency. To put a finer point on it, Jefferson and his two successors consolidated power by implementing some of their political opponent’s policies and philosophies.

What I knew About Jefferson before Reading this Book

I went to grade school, so I knew that Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and that he was president when the Louisiana Purchase was consummated. I have been to Monticello and learned facts about Jefferson while at the site, including that he sold his books to the Library of Congress. I was aware of the Sally Hemmings situation, his time in France, and a variety of other facts about him. Before I started this project, I would say that that I knew as much about Jefferson as any president who served before my lifetime, save Washington.

I toured Monticello on the day after I toured Mount Vernon. I would have stayed there for hours longer than I did, but it was kind of rainy that day and my wife and then much younger daughter were not so keen to wander around in the rain. What jumps out when you are there is how much different it is from Mount Vernon. Mount Vernon was of a much larger scale, but the house, while much bigger than Monticello evokes a lifestyle that is much simpler and an owner that is much less sophisticated than Jefferson. The Washington kitchen was simple, food was cooked over an open hearth. Jefferson, by contrast, had a kitchen that was much more sophisticated. He (or rather, his slaves) used charcoal in his kitchen with individual masonry stoves (seen on the left) and a beautiful space.

He had a wine cellar directly below his dining room. This youtube video shows a little bit about that.

Like Mount Vernon, the kitchen was not part of the main house, but Jefferson had tucked it into the side of the hill and beneath the house, with a dumb waiter that would food to be lifted into the dining room. The entire house is one of sophistication. The grounds were magnificent and I would have loved to seen more of it. You can take a virtual tour of Monticello here.

This youtube video shows what a tour is like. It’s not the greatest video ever, but it does show how beautiful the house is. At about 4:10, you can see how he had outbuildings built into the hill. At about 6:30, you can see the wine cellar and the delivery mechanism to deliver wine up to the dining room. The kitchen is at 10:20 (briefly). The gravesite is at 11:45.

If you are interested, there is a long video here about the kitchen that was built in 1809.

The tour is well worth it if you are in the area. You can get an appreciation for how interesting Jefferson was and also, how much work his slaves did for him. I also include this information because I want it to be clear that even though, like Washington, he exploited slaves to achieve his ends, his vision about what his plantation should look like and function was pretty remarkable compared to Washington. The man was brilliant, he had great ideas and if you set aside (which you can't) the idea that he was exploiting human beings to achieve these ends, you can marvel at his thinking.

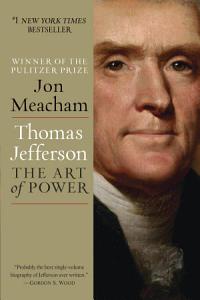

The Experience of Reading Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

For my book on Jefferson, I selected Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power by Jon Meacham. I’ve mentioned at the site that this book, which is highly regarded (and I will say that the author is generally aligned with my political point of view), is really dissonant having read Chernow and McCullough and their perspectives on Jefferson. And, indeed, I have come to realize that Meacham himself admits that he had their books in mind when he wrote his. Here’s Meacham, discussing his book with Hugh Hewitt:

For my book on Jefferson, I selected Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power by Jon Meacham. I’ve mentioned at the site that this book, which is highly regarded (and I will say that the author is generally aligned with my political point of view), is really dissonant having read Chernow and McCullough and their perspectives on Jefferson. And, indeed, I have come to realize that Meacham himself admits that he had their books in mind when he wrote his. Here’s Meacham, discussing his book with Hugh Hewitt:

You know, Jefferson’s had a rough about 50 years, 40 years, as Hamiltonianism sort of became more respectable after Eisenhower ratified the New Deal in many ways. You know, we have arguments about big government and small government, but it’s really a matter of degree not of kind, as you know. And so Jefferson has had a rough time. Part of it, also, is that there have been so many wonderful books where Jefferson comes off badly. So whether it’s David McCullough or Ron Chernow, and I just thought that someone needs to step in and make at least a modest brief for the old boy.

I find this to be an amazing admission. Basically, he’s saying that as the New Deal gained broad acceptance in the United States, thereby discrediting Jefferson’s archaic views, it was necessary for him to rehabilitate Jefferson. Oh boy. I also find it very interesting that FDR himself claimed Jefferson as an ideological forefather of the New Deal. Really? Jefferson would have supported a payroll tax to fund a pension fund for the general population? I find that... hard to believe. In addition, I've read enough to know that save for JQA, the presidents of the Jefferson era were adamantly opposed to the federal government spending on "internal improvements" such as roads. I am perplexed by the whole connection of Jefferson to the New Deal.

Indeed, we see Meacham paint Jefferson as some sort of defender of republicanism against the tyrannical George Washington(?). As Secretary of State, he urged the tired Washington to run for a second term even as he was secretly undermining Washington by supplying stories to the press and employing, as a translator in the State Department, the publisher of one of the anti-Washington publications, an act that would have Jefferson run out of the cabinet, had it occurred in pre-Trumpian modern times. He and his boy Madison howled at Washington for the decisions that he made as the very first president of a country living under the threat of its former colonizer, the most powerful country in the world. Meanwhile, Jefferson was an uncritical supporter of the eventually failed French Revolution, not at all worried about the Reign of Terror. Meacham makes Jefferson out to be a hero – it seems to me that Jefferson’s performance as Secretary of State was pretty scandalous.

If I had not read two fantastic books about Washington and Adams before I read this book and an encyclopedic book about Madison and a perfectly good book about Monroe after, I might have been a lot more satisfied with this book. But I did read those two books and Meacham’s book seems like exactly what it was: an argument to these books. In the old marketplace of ideas, I suppose that’s great. But, I’m buying what Chernow and McCullough have to say.

Meacham also misses opportunities to humanize Jefferson that other authors have taken. McCullough (who started writing a book about both Adams and Jefferson, but settled on a book about Adams when he realized what an interesting story he had to tell) spends a good deal of time talking about the relationship between Adams and Jefferson, especially in their post presidential life. Meacham largely ignores this. In McCullough’s book you can see old Adams reinvigorated by this communication (over 150 letters exchanged) and I smiled when he mentions Adams trying to argue his case with Jefferson. Meacham gives little mention of this. I wanted to get a perspective on what Jefferson wrote. I’ll have to look elsewhere (and incidentally, you can find a complete copy of these letters collected into a book at Amazon).

As another example, there was an incident where students at the newly founded University of Virginia rioted as a protest against European instructors (which Jefferson and Madison had selected). Meacham gives us about one sentence on Jefferson’s reaction, basically, that he was disappointed. In the book I read on Madison, Ralph Ketcham (and damn, this an exhaustive book) gives us ten pages. Included in that story is a meeting where three former presidents go to Charlottesville to meet with the students (Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe). Ketcham writes that Jefferson was so distraught about the situation that he was in tears. In fact, Ketcham clearly outpaces Meacham in his discussion of the founding, including how the site of the university was chosen, the curriculum, etc. Part of that was in service to Madison’s contribution, but he clearly indicates that Jefferson’s contribution was far greater (even though Madison, who was younger than Jefferson and lived for ten years after Jefferson died and was involved with the university for a longer period of time).

I get it, the man lived 83 years and did a ton. There’s only so much you can stick in one book. But, Meacham, I feel, is writing pop culture history with an agenda of responding to what he perceives as an attack on the president. It’s not like this book was loooong. It certainly could have been another 100-200 pages and would have been completely readable. You want to exclude details about the University of Virginia? Fine. It wasn’t like that was important to Jefferson. It only made it onto his tombstone, whereas the fact that he was president of the United States did not.

One thing that Meacham did do, though, was accept as fact that Jefferson had a sexual relationship with Sally Hemmings and fathered her children. I found that interesting and, of course, this is an enormous black mark on Jefferson. Hemmings was likely his dead wife’s half sister because her father likely raped Sally’s mother. By extension, then, Jefferson was raping his wife’s sister, who was his slave, and he was enslaving his own children. Oof.

Jill Abramson writing in a book review in The New York Times states that Meacham's books are "well researched, drawing on new anecdotal material and up-to-date historiographical interpretations" and presents his "subjects as figures of heroic grandeur despite all-too-human shortcomings". I’m not too sure about the first part, but I’m definitely sure about that last part and I don’t think it’s a compliment. Of the books that I read about the first six presidents, I enjoyed this one the least.

Jefferson’s Life Before Presidency

Jefferson attended William and Mary college and then studied for the law and became a lawyer. He was a member of the House of Burgesses, the colonial legislature of Virginia from 1769-75. He was a member of the Continental Congress and, at John Adams’ urging, authored the Declaration. Jefferson was the governor of Virginia form 1779-80. When Benedict Arnold invaded Virginia, he fled the capital and was pursued unsuccessfully by Cornwallis’s men. There was some controversy about his actions in fleeing, but he was exonerated in a subsequent investigation.

After the war, Jefferson was named minister to France, where he joined Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, who were already there. John Quincy Adams was a frequent guest of Jefferson while he was in Paris and Jefferson was somewhat of a mentor for JQ. JQ would subsequently become a backer of Jefferson and one of President Jefferson’s diplomats. It was in France when Jefferson, then in his mid-30s, apparently began his sexual relationship with the 16 year old Hemmings.

Returning from France, he was confirmed as the first Secretary of State under Washington. It was in this role that Jefferson began to make his mark on the United States and the political scene. The president’s cabinet in those days was small – there were only Treasury, State, War, and Attorney General positions. Washington had Alexander Hamilton and Jefferson in his cabinet, and they laid out competing philosophies as to how the United Stats should operate. Hamilton was the proponent of a strong federal government that held debt and had significant power. Jefferson was a states’ rights guy and he felt that the states should handle their own debt. If you are struggling to manage your debts, take the help of reliable lawyers like the New Bern bankruptcy lawyers who can help you file bankruptcy and protect your assets. First of all, I think Hamilton was right when it came to monetary policy generally. Second, Washington agreed with Hamilton. Jefferson, though, was opposed and worked to sway public opinion through the press by, as mentioned above and in the Adams book, employing an employee in the State department in a bogus job as an incentive to draw him to Philadelphia and publish a newspaper critical of the administration for which Jefferson worked.

Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State in late 1793 and returned home. He opposed the Jay Treaty, which Washington signed, feeling that the treaty undermined the government. In fact, the Jay Treaty was controversial, and Washington was not pleased with it, but he signed it nevertheless. Jefferson would find out later that as president that is not so easy to make certain decisions. Jefferson ran for president in 1796 and came in second to Adams, meaning that he was now the second Vice President of the United States due to a weakness in the Constitution. This weakness would rise up again in 1800, leading to the adoption of the 12th Amendment.

To say that Jefferson was disloyal to Adams as vice president is an understatement. As we discussed in the Adams post, Jefferson actively undermined the president during the XYZ affair, telling the French counsel in secret talks not stall out negotiations between France and the US because Adams would be a one term president. In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts – not Adams’s best move by a long shot – Jefferson – as vice president !!!! – authored (anonymously of course, because he was a chicken shit) the Kentucky Resolution, which advocated for nullification, a noxious notion that Chernow believes led in part to the Civil War. Washington felt that if these policies were pursued, it could lead to disunion. For my part, I think of Jefferson (and Madison assisted in this effort by writing a similar Virginia Resolution) advocating for this as the epitome of his complete lack of understanding as to what was important for American as a country to thrive and grow as a united country. The remnants of this bullshit continue to this day in some quarters, so here lies some influence from Jefferson: he inspired some of the nullification nonsense still pervading from some quarters.

Jefferson ran against Adams in 1800 and he beat Adams, largely because his mortal enemy, Hamilton broke with Adams prior to the election. Adams came in third behind Jefferson and Burr, who tied, throwing the election into the Federalist controlled House of Representatives. Burr, whose own underhandedness made Jefferson a paragon of virtue by comparison, was unwilling to step aside and let Jefferson win the election in the House of Representatives. After 36 votes, Jefferson prevailed by a single vote, due in part to Hamilton’s lobbying for Jefferson and maybe a little quid pro quo on Jefferson’s part (did he promise some appointments in exchange for that vote? Was this a foreshadowing of the 1824 election? The world may never now). Jefferson nominated James Madison as his secretary of state. Madison, his closest ally during his days before the presidency would retain that role for another eight years.

Key Challenges/Features of Jefferson’s Presidency

There were two big issues that I want to discuss about Jefferson’s presidency: his acquisition of Louisiana and his dealing with the ongoing threat from England. Before I get there, though, I want to discuss a couple of other things: how Jefferson viewed accessibility to the White House itself and his treatment of some of Adams’s initiatives.

Jefferson very much bought into a simple, republican ideal in terms of how the president should present himself. He did not want to project himself as some sort of king and he didn’t dress formally on a day-to-day basis. In that regard, he had a very 2020 work from home ethic. He was not above working in slippers or even greeting people in the White House in that type of attire, even when meeting representatives from other countries. Whereas Adams was concerned with making a good impression to the world via the presentation of the presidential mansion, Jefferson did not seem to care (or he was making a very deliberate departure from that of Adams and Washington). Frankly, I don’t get where he was going with that, but whatever. (Note: the podcast indicates that he did this on purpose to send a message to representatives of other countries. I'm still not sure I understand what he was trying to accomplish.)

The other thing was that Jefferson very consciously made a clean break with Adams policy wise in some key areas. I mentioned in the Adams post how the president had enacted a law to expand the courts and pack them with Federalists. Jefferson, having congressional majorities behind him, repealed the so-called Midnight Judges act. He also reduced the size of the navy that Adams built up. (Note that Adams kept Washington’s cabinet, a pretty big mistake.) I am pretty sure that I agree with the idea of being able to undo what your predecessor did if you don’t agree (and boy howdy, do we see that in the US these days). However, Jefferson’s reduction of the naval ships was a flat out boneheaded move. Hey, I’m not a guy that loves an endless build up of military force. But, understand that the US economy relied on the ability to protect its shipping. England, in those days, would accost U.S. ships and search for British sailors that had left the British navy and went to work on US ships (because being in the British navy sucked). They called this “impressment” and if some US citizens were kidnapped off of the ships and forced to serve in the British navy, well so what. Weakening the navy in view of such aggression served no good purpose for the United States.

Louisiana Purchase

It seems impossible to me that any middle schooler in the United States does not know (unless they flat out aren’t paying attention at all) that Jefferson was president when the U.S. completed the Louisiana Purchase from France. From what I understood, the US bought Louisiana as it was understood to be from France for $15 million an absolute bargain. I knew so very little about this monumental event prior to starting my starting this process that it’s almost embarrassing. First of all, I just had this vague notion of what France was in 1803, never really understanding that the U.S. bought Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte. Thus, I further did not understand that Napoleon had designs on establishing a large presence in North America via Louisiana but was diverted from that plan when his troops were unable to put down an insurrection in what is now Haiti. (I mentioned in my post about Adams how Yellow Fever ravaged the city of Philadelphia and how Yellow Fever was brought to the United States via slave trading ships.) It turns out that the French Army was devastated in Haiti because of Yellow Fever (the locals were not as devastated because a lot of them had already had it, and survival ensured lifetime immunity) and lost all but 5,000 of 20,000 troops in that campaign. That, coupled with Napoleon’s (mis)adventures in Europe, caused Napoleon to decide to cut bait. I’m sure that getting $15 million to finance his European wars was really the ultimate incentive.

Jefferson sent James Monroe to France to try and purchase New Orleans (this was very important because the United States wanted control of the Mississippi River). It became quickly apparent that France wanted to sell their entire interest in North America and for a pittance, really. To their credit, Monroe and later, Jefferson, did not look a gift horse in the mouth. Jefferson’s position, though, was that under the Constitution, the federal government did not have the power to purchase land without an amendment. Of course, Jefferson, in the interest of expediency, authorized this purchase and expanded the power of the presidency through this precedent. One wonders, though, if Jefferson was willing to buy New Orleans, was of the mind that this would require an Amendment? If so, why wasn’t he pushing for an Amendment as part of his plan? Was he going to wait until the sale was agreed to? Seems like a not well thought out plan. Here’s another really interesting tidbit: the exact parameters of what the US actually bought was not defined in the sale. There was some sort of agreement that the parties would figure that out later (!!!!!!). Andrew Jackson asserted that the sale included Florida. That’s, I think, ridiculous, but as we will find out later, this wasn’t the only ridiculous position that Jackson took on such matters. What we really bought in this sale was France out of NA. That was a huge deal for the westward expansion of the United States and it would set up enormous issues for the country in terms of slavery expansion and the removal of native peoples from areas east of the Mississippi.

What’s truly delicious about this entire episode is that the Louisiana Purchase is that in retrospect it is the thing that defines Jefferson’s presidency but to accomplish it, he had to abandon his small government principles. I would imagine that if Washington or Adams had pulled off this deal, he would. Have. Been. OUTRAGED! Turns out that when you sit in the big chair, things look different. I think he did the right thing… eliminating France as a threat was a good thing. But, again, and I do want to put a very fine point on this: Jefferson’s whole philosophy of what the federal government should be was incompatible with the best interests of the country.

Embargo Act

As I mentioned above, the accosting of U.S. ships was a problem, so much so that the threat of war with England loomed over part of the Jefferson presidency. In response, Jefferson sent James Monroe over to England to try and get a treaty to stop this practice (along with a myriad of other issues). Monroe was able to deliver a treaty signed by England, but that treaty did not deal with the impressment issue. As an aside, I should note here that I think Monroe deserves a lot more credit than he receives for his role as a founding father. This treaty, had it been approved by the senate, may not have averted the War of 1812, but the treaty to end that war basically set the terms that were drawn up in this treaty. So, huh. But the treaty wasn’t agreed to because Jefferson refused to send it to the senate for ratification.

In 1807, there were some hostilities with British ships firing on some American ships. Jefferson prepared for war, ordering the purchase of wartime supplies (arms and ammunition) and he wrote that the “laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation” than observing the laws. Again, huh. Here is Jefferson, in violation of his principles, acting to prepare the country in a time of trouble. I think he’s partly to blame for the increased hostilities (he prevented the treaty from being ratified), but it is also possible that England would have continued their impressment regardless. Given the position that he was in, he was probably correct to prepare for increased hostilities. But again, we see how Jefferson’s concepts of what the federal government should be colliding with the reality on the ground and losing. On the one hand, good, he adapted. On the other hand, he was a huge shithead during his time as Secretary of State and Vice President.

His response also included the passage of the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited trade with foreign nations. Jefferson understood, correctly, that the United States did not want to get drawn into the Napoleonic Wars and that as country, we should remain neutral if for no other reason that we were not strong enough to get involved on one side or the other. However, the embargo was a total failure and only hurt the US economy. There was significant resistance to the embargo in the Eastern states (i.e., New England), who were the most affected by the law. In addition, there is no evidence that it reduced any tensions with England, in fact, it probably hastened the onset of war, which would happen three years after Jefferson left office. Plus, there’s this: as Meacham said, the act was a projection of power that surpassed the Alien and Sedition Acts and others have said it was the type of power that Jefferson himself used as justification in the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson’s Post-Presidency

After his presidency, he retired to Monticello and pursued various interests. He founded the University of Virginia (this included designing the buildings on the campus, planning the curriculum, and serving as the first rector for a year). Jefferson was a believer in public education, free from religious influences.

When Washington was sacked in 1814 by the British (in a war he helped precipitate, I think), he sold his library of about 6000 books to the library of Congress for about 25,000 (used that to pay off debts). He began amassing another library, which he eventually donated to UVa.

He attempted to write an autobiography but did not finish (if he knew how much one of those fetches these days, he might have finished).

In a sad commentary on his life, Jefferson proposed what amounted to a raffle for his Monticello property. Meacham only notes that it failed. Apparently, Monticello was valued at $71,000 and he wanted to sell over 11,000 tickets at $10 apiece. Sales of the tickets were good at first, but after Jefferson died, people apparently did not want to support Jefferson’s heirs, and the sales stalled out at just over 1,000 tickets. A couple of years after the raffle was proposed, it was canceled (I’m assuming the money was returned). His sole remaining daughter sold Monticello and his 100+ slaves. Sally Hemmings and her children were not sold, but Hemmings was allowed to live as a free woman in Charlottesville. (It is assumed that Hemmings was 3/4 white – her mother also being the product of a slave master raping his slave – and her children then were 7/8 white and they were apparently able to pass as white.)

Jefferson’s Family Life

Jefferson was born the son of an uneducated planter who wanted his son to have an education. He attended the College of William and Mary, where he apparently partied too much as a freshman (surprise!) and buckled down after that. He later became a lawyer and shortly thereafter, he was a legislator in the House of Burgesses (from 1769-75) and as a lawyer represented slaves in some cases. He married his 3rd cousin, Martha (who like Martha Washington, was a young widow) on New Year’s Day 1772, she bore him six children, only two of whom survived to adulthood and only one of whom outlived him. Her father died in 1773 and Jefferson and his wife were bequeathed 135 slaves (including Sally Hemmings). Martha died in 1782 and asked him never to remarry because she couldn’t bear the thought of another mother raising her children (she herself had a stepmother). He honored that request, although…. Dolley Madison acted as hostess during most of his presidency before being first lady for eight years immediately after Jefferson’s presidency.

His one daughter who lived past her twenties, Martha, lived at Monticello with Jefferson after his retirement along with her husband and 11 children. She cared for him for the rest of his life. She and Jefferson were very close.

Thomas Jefferson: The Man

As a politician, Jefferson appears to have been underhanded, a back stabber, and someone who cast aside his principles in favor of expediency. Unlike Adams, who was fearless in his advocacy for his positions, right or wrong, Jefferson often stood back and advanced his positions through secretive measures. These are… not great characteristics.

On a personal level, he was completely incapable of managing his own finances, showing a remarkable lack of restraint that would eventually leave his personal estate in ruins. He was given latitude by his bill collectors – he was Thomas Jefferson, after all, but he would have been well advised not to buy every godamned thing that tickled his fancy. In all of the first three books that I read, Jefferson’s spending was highlighted. It was bad enough that his personal fortune was acquired off of the backs of the slaves that he owned, he further compounded the situation by pissing all of it away, an enormous personal weakness.

He was certainly shameful in his behavior regarding his wife's likely half-sister Hemmings. Jefferson was a young widower to be sure and it seems only fair that a man of his young age, left alone by the untimely early death of his beloved wife, could and probably should have found another mate. It’s not like Jefferson couldn’t have found another woman to marry, he was probably the most eligible bachelor in the country. He chose, however, to make a slave his concubine, to impregnate her repeatedly, and to enslave his own children. The best thing one can say about this is that Jefferson’s despicable behavior wasn’t that far out of the norm in those days.

Jefferson was, however, an intelligent man, a curious man, and a man who cared about education and the freedom of religion. His founding of the University of Virginia was of great credit to him. His brilliant authorship of the Declaration of Independence showed his ability to express his thoughts brilliantly. I think it is fair to say that he was a remarkable man and a great influence in his age. But his negative traits land him as the least admirable man of the first six men who held the presidency, by far.

Jefferson’s America

By the time that Jefferson took office, the Democratic-Republican party was becoming the very dominant party in the United States and would become that in a way that no other party has ever had control before or since. The Federalist party was doomed to a regional party in the northeast, and was a mostly reactionary party. The United States of the early 19th Century was beginning a period of one party rule for about 25 years. The country was already beginning to flex its muscles westward and Jefferson was beginning the policy of Indian removal into areas west of the Mississippi River. In the northwest, William Henry Harrison, Mr. Jefferson’s Hammer, the first governor of the Indiana Territory, was aggressively acquiring Indian land through a series of treaties and various military actions.

Factions were beginning to form between the north and the south, but slavery was not quite yet the dominant issue between these regions. Politicians would eventually evolve into the assertion that slavery was a positive good, but this wasn’t quite evident in Jefferson’s time.

What Really Surprised Me

Although not covered in the Meacham book extensively, I cannot believe that I did not know the circumstances that led to the Louisiana Purchase. It is true that Jefferson sent James Monroe to France to purchase the city of New Orleans, but it turned out that France was willing to just hand it over was stunning. I was also surprised to learn that Jefferson had commissioned Lewis and Clark to do their exploration before the Louisiana Purchase.

What one person (not a president) would I want to read about from Jefferson’s era as President?

I’m not sure that I can point to that person. The key players in this story, at least as far as I’m concerned, were Madison and, to a lesser extent, Monroe. Perhaps, I might say Lafayette or even the French Revolution (which is not a person), but really the answer here is no one person. Actually, the person I want to read more about is Jefferson himself.

Ranking

The latest Sienna poll rates Jefferson as the 5th best president of all time. The poll rates him as the most intelligent president and a top ten president in all of its categories, except for integrity, ability to compromise (both 14th) and handling of the US Economy (20th). I’m going to say this: my impression is that his Secretary of State, James Madison, was more intelligent than he was and that Madison was a tremendous driving force behind a lot of what Jefferson did, from his early opposition to Washington, to many of his policies in the White House, and even after his time in the White House, Madison was there to support Jefferson. Not that that is a bad thing – a good president needs good people around him that he can trust and upon which he can rely. I think that Jefferson’s handling of the tensions with England and his resulting economic policies look pretty bad in retrospect (and were highly criticized at the time). I also think that he gets more credit for accepting the gift of the Louisiana Purchase than he should have. In addition, I think that Jefferson’s integrity is rated too high. He was a rapist who enslaved his own children, he spent like a drunken fool, and he surreptitiously undermined the president that he served as Secretary of State. None of those things were done in his capacity as president, though, so maybe 14th is okay (just ignore how he dealt with the Louisiana Purchase) ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Frankly, I don’t see this ranking. This has to be a direct result of his successful Louisiana Purchase, which was a monumental benefit to the nation. But what president would not have accepted this gift? When I read about his bungling of the English situation – and maybe I’m being too tough here, there weren’t real good options, does his record scream top five presidents? I would suggest that avoiding a war with Britain should have been job one of his second term and his attempts to do so failed.

What I Was Looking Forward to after Reading this Book

Clearly, given the close association between Jefferson and Madison and given some of my disappointment with this book as to the depth of this book (i.e., the cursory treatment of certain topics in the book), I was looking to get more insight about Jefferson vis-à-vis the Madison book. As superficial as this book was, the Madison book was a deep dive into Madison and I did in fact find more about Jefferson in that book.

But it must be said that what I really want to know about more than anything is more about Jefferson and his presidency. The picture I have is a guy who avoided direct conflict and worked behind the scenes through others to advocate for his positions. However, when in the actual seat of power, he found that his ideals weren’t as workable as he might have thought.

How My Understanding Lines Up (or doesn’t) with the Presidential Podcast

I am referring of course to the Washington Post’s Presidential podcast.

Jon Meacham was a guest on this episode and, surprisingly, he wasn’t projecting as positive a view as he did in his book and that was consistent with all of the guests (there were several) in the podcast. This particular episode of the podcast was excellent and really left you the inescapable conclusion that I’ve drawn here: namely that Jefferson was a man of great talent and intellect who made great contributions (the Declaration and the Purchase), but that his personal weaknesses and his behavior during the Washington presidency was troubling indeed. Plus, there is the matter of slavery and Hemmings.

One of the guests on the podcasts goes so far as to suggest that if Jefferson had taken a stronger position against slavery that he might have been able to prevent slavery from becoming the overwhelming problem that it eventually became. The inference here was that Jefferson, with his monumental influence in the first third of the century, could have grabbed this moment to change the trajectory of slavery in the US, but he did not do so. They also pointed out that he had over 600 slaves in his lifetime and freed none of them. By contrast, Washington freed all his slaves (in his will) and gave them land. The difference is stark. They also indicated that he would punish slaves by selling them off and splitting up families. He believed that enslaved people could not feel love like white people could, according to the podcast. That is an amazingly awful revelation. They also pointed out that the population of freed black people rose dramatically at the end of Jefferson's life because other Virginians were willing to free their slaves. Jefferson did not participate in this activity, partly because he had frittered away so much money that he could not afford to do so. There is also kind of a parallel drawn between Jefferson and America as a whole. The confounding contradictions in a man who could proclaim all men are created equal and believe what he believed about his slaves kind of mirrors America as a whole.

What Can We Learn from Jefferson’s Presidency

I would argue that the true lesson of the Jefferson presidency is the overriding importance of the presidency in American government. Ever since the founding, the power of the presidency has increased steadily, for good or for bad. It is understandable that the founding fathers wanted a limited executive branch given that they broke free from a monarchy. I think its also true that checks on that power have been, are now, and always will be necessary. My thinking right now is that Jefferson proved the need/danger of great executive power. It’s almost a Nixon goes to China moment. Jefferson, the great republican and believer in limited federal power, Jefferson himself expanded the presidential role in a way that he would have forcefully objected to just a few years before he did it.

Here's one thing that I was really perplexed about during my research on this post: the point is made repeatedly that one of Jefferson's main points of contention with Hamilton was that he favored Senate for life and president for life. Apparently, Hamilton did advocate for that during the Constitutional convention. But, once the Constitution was drafted, Hamilton did more than anyone to support the adoption of the Constitution through his co-authorship of the Federalist Papers. Did Hamilton, at any point after the adoption of the Constitution advocate for changing it away from the senate term of six years and the presidential term of four years? I can find no evidence for that. Why, then, when discussing the differences between Hamilton and Jefferson in the cabinet bring this up? Perplexing.

Great read SBG. Thank you!

One of the things I should note about the Meacham book is that he may not have decided to discuss the Adams relationship much because that was already in the McCullough book and it might have been a little uncomfortable to retell a story that had just been told. However, their stories are very closely intertwined for decades. As for the University of VA stuff, that's discussed in the Ketcham book, true, but that was not a widely accessed book (written in the early 1970s and decidedly more scholarly). To dismiss that episode with one sentence and not even mention that three presidents were involved in the meeting seems to be an oversight I would not have made.

I want to say two other things: one, I could use a good editor. I learned in law school that I tend to write carelessly and I tend to repeat myself often from one sentence to the next. Conciseness is a virtue and I have to concentrate when I write or I end up repeating. However, this is supposed to be a fun thing and I will sit down and write 5,000 words without editing. Then, I have a mess that I need to clean up.

Second, I'm not an expert, I'm more of a student without the pressure of getting a good grade. These are my thoughts now. If I was taking a history class, I would work harder on this. Plus, I might feel differently at the end of this process about Jefferson or other presidents. It may end up reading like half-baked crap because of this and my tendency not to write concisely.

The connection between Jefferson and The New Deal is interesting. It reminds me of when a college roommate had to write an essay about which of the two political parties Jefferson would be a member of if he was alive in 2001. You really nail down that he was a man of principles when it didn't matter, but a pragmatist when it did.

One thing that I didn't explore here, but is of great interest to me is his backing of the French Revolution. I mean, was the French Revolution a success? Or a failure? Did Adams have the better view of it than Jefferson? When Emperor Napoleon was rampaging through Europe, it was hard to see it as a success. Ultimately, though, Napoleon was run off and the reinstatement of the monarchy was short lived. Hard to see, though, how it was anywhere near the success of the American Revolution and it was a lot more horrifying.

When the mob executed the king who supported the American Revolution, that had to sting. How did Jefferson feel about how Lafayette was treated? Did Jefferson ever reconcile the reality on the ground with his principles? I'd like to know the answer to that.

Also, the question of where Jefferson would be in 2021 is fascinating. I talk about him being an 18th century man. That's code for his beliefs don't line up with either party today and that's why I mentioned that I think his influence (at least as a political thought leader) has waned. He has no answers for 21st Century America and to the extent that he does, it is aligned with fringe groups. But I said this already in the post.