I have been making some pretty good progress lately on my quest to read one book on each president. Currently on #22 and #24, Grover Cleveland.

All posts by SBG

SBG’s Presidential Biography Tour: James Madison, 4th President of the United States

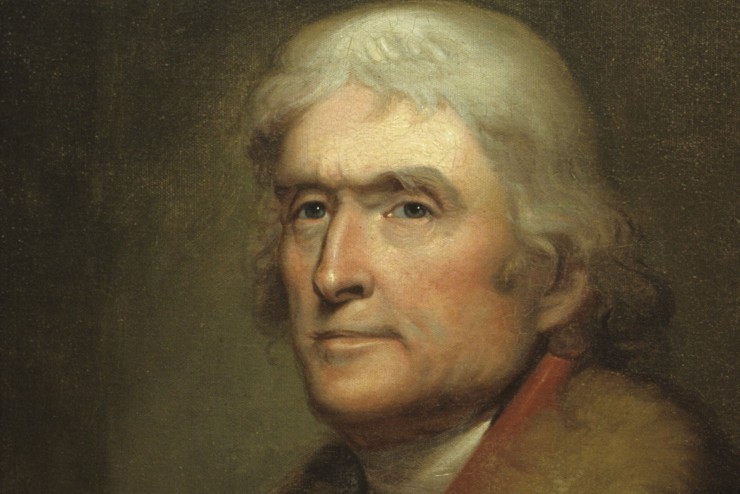

Welcome to the fourth installation of my journey through the presidency via presidential biographies. Today, we discuss James Madison, the fourth president and more importantly the primary author of the Constitution. Madison was the first wartime president and was another president of the early period of the United States that could never, ever, ever be elected president in the 21st Century. (I think of the first four presidents, only Jefferson would likely be able to obtain the White House today.)

I am writing these essays primarily for myself to kind of solidify my thoughts about these men, the times in which they lived, and how they impacted the United States. The fact that I’m publishing them, though should indicate that I want to share my thoughts with you, too. Even if none of you read these articles I will write them. But, if you do read them, I’d appreciate a comment or a question as it does provide some additional incentive to keep going. 😊

Background

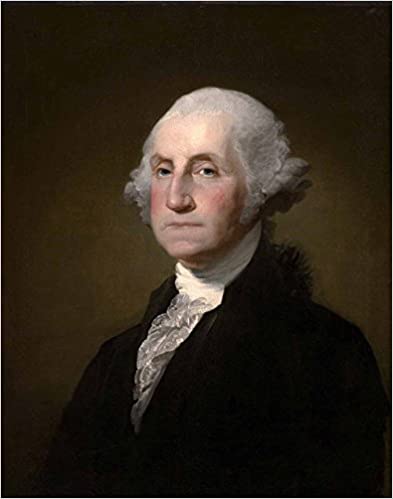

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Belle Grove, Virginia and he died on June 28, 1836 at his home Montpelier, in Virginia. He was president from March 4, 1809 to March 4, 1817, having won the 1808 and 1812 elections. Madison is best known as the primary author of the United States Constitution and Thomas Jefferson’s chief ally and, I would argue, the substantial intellectual force behind the republican movement. George Clinton, Jefferson’s second vice president remained in that role at the beginning of Madison’s presidency, but he died on April 20, 1812. The vice presidency remained vacant until the beginning of Madison’s second term (note that it wasn’t until the 25th Amendment – adopted in 1967 – that a vice president could be replaced by nomination of the president and confirmation by the both (!) houses of congress). Eldridge Gerry was the fifth vice president, serving from March 4, 1813 until he died on November 23, 1814. Both of Madison’s vice presidents died in office! Interesting aside: the practice of gerrymandering is named after our fifth vice president. Also, they had virtually no role in the Madison presidency and will not be mentioned by name again in this piece.

We had an exceptional run of presidents in terms of their experiences prior to being president. Those of us who are old enough to remember George H.W. Bush remember that his resume was a selling feature of his campaign. Likewise, Hillary Clinton touted her resume. Oh yeah? Did you folks write the Constitution of the United States? Were you a member of the First Congress of the United States? Did you hold the office of Secretary of State when the United States completed the Louisiana Purchase? No? Well, sit down then.

What I knew About Madison before Reading this Book

I knew that Madison was president during the War of 1812, that he was the primary author of the Constitution, that he was really short, and that his wife was highly regarded as a first lady who still hawks Zingers cakes to this day. As I have mentioned before, I visited both Mount Vernon and Monticello, but I did not visit Montpelier. I had only two days reserved for visiting presidential mansions. I did see signs advertising Montpelier, but we did not go. I now regret that.

The Experience of Reading James Madison: A Biography

The book that I selected to read about Madison was James Madison: A Biography by Ralph Ketcham, which was first published in 1971. The book is 671 very dense pages, exclusive of the end notes and is fairly small print and it may be longer than the 818 page Chernow book on Washington. I finished the book on February 28, 2021. This book is not at all like the first three books that I read. I think that part of this is because Chernow, McCullough, and Meacham wrote books that are intended to be read by a wide audience. Ketcham, a professor, probably wanted to have his book read by a wide audience, too, but I think he was more focused on a more scholarly account of Madison (although it is only 671 pages, so…). Make no mistake, though, Madison, unlike the first three characters of this book, was not a larger than life figure. He was studious, reserved, not as… interesting. While this book is not as accessible, it is still a very well written book. Madison, as Jefferson’s right hand man, comes off as underhanded in the Chernow book especially. This book, written 40 years before Chernow’s provides what I think is a pretty fair assessment of the fourth president. I should note that this is the last book that I read where I didn’t take any notes, and honestly, I’ve forgotten a lot of the details of the book now. I simply don’t have enough time to go back and do research or re-read the book. In the interest of keeping this series going, I will simply acknowledge that and move on.

The book that I selected to read about Madison was James Madison: A Biography by Ralph Ketcham, which was first published in 1971. The book is 671 very dense pages, exclusive of the end notes and is fairly small print and it may be longer than the 818 page Chernow book on Washington. I finished the book on February 28, 2021. This book is not at all like the first three books that I read. I think that part of this is because Chernow, McCullough, and Meacham wrote books that are intended to be read by a wide audience. Ketcham, a professor, probably wanted to have his book read by a wide audience, too, but I think he was more focused on a more scholarly account of Madison (although it is only 671 pages, so…). Make no mistake, though, Madison, unlike the first three characters of this book, was not a larger than life figure. He was studious, reserved, not as… interesting. While this book is not as accessible, it is still a very well written book. Madison, as Jefferson’s right hand man, comes off as underhanded in the Chernow book especially. This book, written 40 years before Chernow’s provides what I think is a pretty fair assessment of the fourth president. I should note that this is the last book that I read where I didn’t take any notes, and honestly, I’ve forgotten a lot of the details of the book now. I simply don’t have enough time to go back and do research or re-read the book. In the interest of keeping this series going, I will simply acknowledge that and move on.

Madison’s Life Before Presidency

Madison was born into a wealthy family in Virginia and he was a distant relative of the twelfth president of the United States, Zachary Taylor. Madison attended what is now Princeton University and was an excellent student. He was a member of the House of delegates and of the Continental Congress during the war. Madison was seen as frail and of poor health (he lived to be 85 in early America!) and he never served in the war.

Madison was a member of the first House of Representatives of the United States, and he won his seat in Congress by beating some dude named James Monroe (yes, that James Monroe). Monroe is seen generally as an ally of Jefferson and Madison and, as the fifth president of the United States, he generally carried on the Jeffersonian tradition. But, in 1788, he was an opponent of Madison’s (and a favorite of some sectors in Virginia politicians including Patrick Henry who were anti-federalists, that is, opposed to the new Constitution – that seat was gerrymandered to help Monroe), but not a successful one. Some people in the Democratic-Republican party wanted Monroe to challenge Madison for the presidency. That did not happen, of course. Madison teamed with Jefferson to challenge the Washington administration’s policies and Madison shamefully wrote the so-called Virginia Resolutions, a companion to Jefferson’s Kentucky resolutions, advocating for the poisonous idea of nullification of federal laws by the individual states, a virus that remains in circulation until this very day.

Madison was also Jefferson’s Secretary of State and he, along with Jefferson, disapproved of Monroe’s negotiations with the British in a treaty that Monroe signed but was never presented by the Jefferson administration for ratification by Congress. The Jefferson administration felt that the treaty was a failure because it did not end the British practice of impressment. The British would board US ships and try to recapture British sailors that had abandoned the British navy to join US merchant ships. In the process, the British would nab Americans and force them into the British navy. Eventually, as president, Madison would initiate a war over this issue, the War of 1812. Madison, in his capacity as Secretary of State was a party in the most consequential Supreme Court decision of all time. There was one other thing: he was Secretary of State when the US purchased Louisiana from France, although Madison didn’t really have much to do with that. He sent Monroe to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans and he went off and bought the whole damned thing. It’s kind of like going to Target for paper towels and coming home with a car full of stuff.

Of course, Madison’s key contribution to the United States before he became president was his role in authoring the United States Constitution. Madison understood that the early American government was weak and ineffectual and recognized the need for a strong federal government, or at least a stronger one than existed. Madison was a primary author of a so-called Virginia Plan, which was the framework upon which the United States Constitution was drafted. Alexander Hamilton convinced Madison to help author the Federalist Papers after Madison had urged members of Congress (he was one) to remain neutral in the ratification process. There was a surprising amount of resistance to the new Constitution (you may remember that Washington was president for over a year before all of the states ratified it). The whole Constitutional debate is very interesting … some were opposed to the new Constitution because the Constitution as originally ratified was focused on the powers of the Government and not the liberties of the people (i.e., there was no Bill of Rights). Others felt that a strong central government would not be good for the individual states. Madison himself wrote the Bill of Rights, which further cements his legacy as one of the most important founding father.

Madison ended up being an effective advocate for the ratification in his home state of Virginia, where significant resistance existed. I am not going to write about the Constitutional debate in detail here, because I would have to go back to the book and reread it a fair amount. But, one of the key touchstones of the original Constitutions was the 3/5ths Compromise. In the 21st Century, this concept has become shorthand for how black people were considered less than fully human. And indeed, it looks pretty awful 200 years after the fact. But I would submit that this is much less odious than, you know, allowing slavery in the first place. Northern states did not want enslaved people counted at all for the purposes of taxation and, more importantly, representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. The southern states, of course, wanted their slaves to be counted for representation purposes. The 3/5ths Compromise, first proposed by Madison, to count 60% of the slave population for taxation and representation purposes. It sounds very bad. In practice, it was very bad in those days, because it granted more power to the slave states to perpetuate policy to maintaining slavery, both in the House of Representatives and, of course, in the White House because of the electoral college. Bad as a symbol and bad as policy. Some historians have said that if slaves had not counted at all in the matters of taxation and representation, Adams would have won the 1800 presidential election, there would have been no slavery in Missouri, Jackson’s Indian removal policy would have failed and various other pro-slavery acts would have failed. In other words, counting slaves as 3/5ths of a person – instead of not at all – actually perpetuated slavery in the United States. I realize that this is a complex issue and slavers were not going down without a fight. But, man.

I’ve heard the notion in some quarters that the Constitution was divinely inspired. Not seeing that.

Key Challenges/Features of Madison’s Presidency

Madison started with an ineffective cabinet, especially in the Secretary of State role and Madison basically distrusted his cabinet. He made a key move early on, though, and installed his frenemy, James Monroe as his 2nd Secretary of State. I’ve come away from this period believing that Monroe was vastly underrated relative to Jefferson and Madison – he may not have had the same intellectual prowess as these guys, but he was a doer and he saved Madison’s hide. Monroe was not shorted in the old ambition department, but we will get to that next time.

The key challenge of the Madison presidency was handling the ongoing conflict with England. As Jefferson’s right hand man, he had supported Jefferson’s disastrous embargo law, which forbid any foreign trade and the subsequent policy of only forbidding trade with France and England. The United States’ position in the ongoing warring between France and England was to be neutral. Madison then attempted to pit England and France against each other by trying to establish trade with one party or the other if they agreed to stop attacking American ships. Napoleon agreed to a contingent deal with the US and Madison thought that the British would follow along, but they didn’t and Napoleon reneged (huh). As an aside, the British navy was the undisputed power in the Atlantic. Napoleon had ground force superiority, but the idea that they were somehow equals in the water was absurd.

With conditions not improving, Madison decided that war was the answer. He figured (heh) that with England off fighting Napoleon, the US could just march in and take Canada as a bargaining chip (or as just an expansion of the United States). Congress was behind Madison, so they started a military buildup and eventually, at Madison’s request, declared war on the most powerful country on earth.

I want to stop right here and editorialize. Madison was a pretty smart guy – I think he was the intellectual equal of any president of the first five presidents – but he was completely deluded. The United States did not have a standing army. The United States did not have military leadership capable of matching up with the British. Hell, they could barely handle small Indian tribes. And James Madison thought that they could just kick England’s ass. Unbelievable. Washington probably started spinning in his grave.

Madison’s idea was that the US would attack the British at Detroit, knock them out there and that the northern states’ militias would just push into Canada. He apparently forgot to check in with the northern states who, under the 2nd Amendment, had guns for their well(?)-regulated militias. Turns out that the northern states didn’t want to participate in this war. Detroit fell to the British without a shot fired. No invasion of Canada happened. Madison’s Canada campaign was a complete failure. In addition, Madison didn’t have any funds to mount a fight. So, again, he declared war without an Army, any sort of real plan and no money to pay for it. I mentioned above that his cabinet was ineffective and that was especially true of his War Department. Madison replaced his War Secretary with another incompetent (a fellow named John Armstrong) and eventually turned to Monroe to run both State and War and Monroe proved to be his most effective War Secretary. Armstrong failed to defend Washington, D.C., despite the presence of the British fleet in Chesapeake Bay, thinking that they would head to Baltimore instead of, you know, the nation’s capital. Washington was sacked, the White House and the Capitol were burned and Dolley Madison saved Washington’s portrait. Madison himself had to escape capture on horseback.

Shortly after the war started, Russia offered to broker an agreement with England and Madison sent John Quincy Adams to negotiate. Turns out, though, that the British weren’t so eager to meet. As the war went on, the US did win some battles, and a young general named William Henry Harrison scored victories in what was then the Northwest and Andrew Jackson was victorious in the West. But the British were still pounding the US pretty effectively (see the paragraph immediately preceding this one, where I discuss the sacking of Washington). However, the British were held off at Baltimore (hey, maybe the strategy worked!) and turns out that the British public was not in favor of blowing cash and their young men in foreign misadventures. Eventually, a peace deal was hammered out in Europe the terms of which were similar to those in the treaty that Monroe had negotiated in 1806.

After that treaty was signed, but before anyone knew that in the US, Andrew Jackson scored his huge victory in New Orleans, and the public eventually believed that the British were forced to negotiate because of the glorious victory in New Orleans. Not true, but Madison’s popularity improved post war. So, was the war worth it? On the one hand, the US entered a war with grand designs, no real war plan, and without any sort of army that could actually fight directly even against a British army that was distracted by the French in Europe. The terms of the treaty could have been achieved a decade earlier, had Madison and Jefferson backed the treaty that Monroe negotiated. On the other hand, I think the British realized that they didn’t want to be fighting wars in the US every 25 years. War is expensive and the British realized that they couldn’t actually control the American continent anymore (I think this point is made in the book I read on Monroe, actually). So that was a benefit. Add in a misunderstanding of the real import of the Battle of New Orleans, and you had an American people who believe the war was a great success.

But ultimately, the threat on the seas ended when Napoleon met his Waterloo. France was defeated and the primary threat to England – France – was removed. That would have happened without the War of 1812. In retrospect, this looks like a war that could have been easily avoided. Would the British eventually mounted another campaign in the US? Hard to say. But, 200 years after the fact, it’s hard to say that Madison did a good job conducting this war or preparing for it. Nevertheless, he reaped benefit for it.

Madison weathered the war amazingly well, he would not have done so in more modern times, I would think (then again, the US military of the 21st century is a little more organized than what Madison had in 1812). Madison, unlike Jefferson, was much more of an adherent of limited government principles. Reading about Jefferson 200+ years after his presidency, I could both point to his willingness to set aside his principles for the sake of expediency and applaud him for recognizing that the definition of the federal governmental power was going to need revisiting as the country grew. It is also true that relying on Constitutional Amendments was not going to be an effective way to grow the federal government as it needed (I think) to grow. Damn it, the Louisiana Purchase was a good idea and waiting around for Constitutional Amendment might have prevented it from happening.

Madison was not so pragmatic. He was in favor of spend federal government money on so-called internal improvements (infrastructure!). At the end of his presidency, the Congress had an Infrastructure Week and passed a bill for internal improvements, including projects that Madison favored. With four days left in his presidency, Madison vetoed it. He felt that the bill was unconstitutional – he thought that the Congress needed an Amendment to the Constitution before it could make such improvements. Note that this was post Marbury v. Madison when the Courts had asserted their power to make such determinations. No president after say, 1829, would ever veto a bill on such grounds. One wonders, then, if Madison’s objection to the Alien and Sedition Acts were because of the policy or the Constitutionality? No president would veto a bill because they simply didn’t like the law until Andrew Jackson. Would Madison have objected to an Adams veto here if he felt the Acts were Constitutional? I think he may have.

This kind of thinking, while perhaps noble I suppose, did the US no favors. I would argue that having the federal government finance the building of roads and bridges to make travel a little less formidable might have impacted Commerce between the States. Having the author of the Constitution weigh in on the side of such laws being consistent with the powers of the federal government might have pushed the United States into a different direction. I haven’t read about presidents beyond 1841, so I don’t know if such ideas have come up after that. 😉 But, supposing they did, I would imagine that they would have been contentious – just how far could Congress go in regulating Commerce between the several States? Stay tuned, we will find out if that ever happened!

Madison’s Post-Presidency

After he retired, Madison moved back to Montpelier and lived out his life (he would live 19 more years). He largely stayed out of presidential politics, including the contentious election of 1824, but he was available for advice to presidents. The Ketcham book discusses some about Madison’s effort to burnish his legacy by altering some of his earlier papers. Other sources suggest that his “efforts” here were somewhat of an obsession. It is… unfortunate that he would do such a thing. Madison was also a part of the rewriting of the Virginia constitution in the late 1820s.

Like Washington and Jefferson before him (and Monroe after him), he left the presidency a much poorer man than when he entered it. On the one hand, I see this as a shame. I’m not in favor of making presidents fabulously wealthy on the taxpayer’s dime, but I do think a reasonable pension is good policy. Madison was not a spendthrift like Jefferson, he suffered a lot because of his step-son’s financial irresponsibility. On the other hand, Madison was wealthy in the first place because of his inheritance of a slave plantation (so hard to feel sorry because of the ownership of humans) and the decline of Virginia plantations due to the impact that tobacco had on their farmland and falling tobacco prices affected that entire region, not just the former presidents.

Madison’s Family Life

Like Washington, Madison married a young widow and did not have children of his own. Unlike Martha Washington, though, she did not bring Madison wealth and indeed, her son was a tremendous financial strain on Madison.

Madison was not, unlike any of his predecessors, much of a ladies’ man and he did not marry until he was 43 years old. Ketcham writes about a romance that Madison had with a young woman when he was in his mid 30s with a 15 year old girl. Madison was apparently an awkward suitor and unable to convince this child to marry him. The idea that a 35 year old man would be courting a pubescent girl is pretty gross to contemplate in modern times. However, I’m not sure it was all that unheard of back then, and it further highlights the ways in which our society has evolved. I’m not saying that Madison was some sort of Matt Gaetz, but what I am saying is that Gaetz would have significantly fewer problems had he lived 200 years ago.

The story is that Aaron Burr was the person who introduced Dolley Madison (and there is some confusion as to the spelling of her first name, but Dolley is what Ketcham uses) to Madison and the general feeling is that Madison was quite happy with his mate. Dolley was a very popular first lady and a great asset to the president. While Madison was seen as somewhat of a dour figure, his wife was a great entertainer. There were some rumors of Dolley being unfaithful, but those rumors were mainly forwarded by Madison’s political opponent.

Madison cared for her son even when he was an adult and a financial burden. It is interesting that Washington, Adams, and Madison all had children or step-children that were huge financial burdens. These guys were probably not great fathers – they put their careers ahead of their families. The picture painted of Madison the retiree was more flattering in that regard. Once retired, family becomes more important, I guess.

An interesting side note not covered in the book: in his will, Madison left a fair amount of money to various causes, leaving only $30,000 for his wife (I think he thought he had more than that left). She lived another 13 years after he did and would up pretty much destitute. Daniel Webster, in an effort to help the former first lady, bought her personal slave and freed him. There she was, basically destitute, but she still owned another human being. Truth be told, after a lifetime of involuntary servitude, her slave likely had nowhere else to go.

James Madison: The Man

Madison appears to have been the classic high minded intellectual: aloof, awkward around members of the opposite sex, and wrestling with complex ideas without an instinct towards pragmatism. And yet, he was enormously influential in early America. He provided a framework for the Constitution that, despite its limitations, was a profound improvement over the government that preceded it. He was like a one-man think tank for Thomas Jefferson and his ideas impacted how America operated for a very long time. As president, he struggled in his role as commander-in-chief, the exact type of role that an intellectual is going to struggle in. Given the lack of a real military leadership, more responsibility fell on him than might otherwise and I think he was not particularly good at it.

As I mentioned above with regard to his Infrastructure Week moment, I think Madison could have benefitted the country with a little of Jefferson’s pragmatism. I don’t want to dismiss Madison’s (I think, incorrect) decision to veto that bill out of hand. Madison was wrestling with a profound concept: just how powerful should the federal government be? He certainly, as an architect of the Constitution, was a proponent of a stronger federal government than we had, but he also recognized that the power of the federal government could grow to far. He wrestled with that in real time, without the benefit of 200 years of hindsight, and he wrestled with it in a principled, good faith way. I do not have the impression that he was deceptive or underhanded in the way that Jefferson was. Madison was at one time contemplating the clergy as a vocation and I think he was earnest in his convictions. Today, Madison would probably not have a role in today’s political environment. He would be an intellectual pillar for some political movement (although, I’m not really sure which one).

We cannot discuss these people without mentioning that they owned other human beings. Madison was in favor of ending slave trade at the time of the Constitution, but of course, there was a twenty year moratorium for limiting slave trade in the Constitution (not sure how Jesus came down on that one). He was, in later life, against the restriction of additional slave states and his 3/5ths Compromise extended power to the slave states. Further, while he wasn’t as hawkish on Indian removal as Andrew Jackson, he did believe that Native Americans were savages who couldn’t assimilate into the American agrarian culture.

Madison’s America

The United States of 1809-17 was both on an expansionist course to dominate the continent and a poorly run collection of small states that were often in active competition with each other. On the one hand, the United States (kind of) extended past the Mississippi River (it was going be Monroe – there’s that guy again – that got a more definitive answer as to what, exactly, the Louisiana Purchase included). William Henry Harrison was pushing the natives out of the old Northwest (Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Indiana). Meanwhile, the New England states were off on their own agenda, trying to perhaps reconnect with England and certainly not interested in participating in a national effort to win a war on American soil against the British. This action in New England was more of a death rattle of the old Federalist party than anything, though. By the end of Madison’s presidency, there was the forming of a national consensus on a lot of issues (not slavery). Madison supported the establishment of a Second National Bank (a Federalist concept that Hamilton at one time opposed) and financing of the Cumberland Road. In other words, Madison helped to kill the Federalist Party by supporting its most popular ideas and opposing the whole let’s get back in bed with England part. He could have gone the final mile in signing the internal improvements bill at the end of his term, but he didn’t. (Monroe was much more supportive of internal improvements.)

What Really Surprised Me

It was very surprising to me that northern states were not supportive of the War of 1812 and they would not provide military support to that effort. It is also really surprising that this support was not ensured before declaring war. It really reinforces to me that even almost 40 years after the founding of the Country, America was still a backwater country with a weak federal government.

What one person (not a president) would I want to read about from Madison's era as President?

I’m not sure I know who this would be, as Madison’s life was dominated by his interactions with Jefferson and the sometimes partnership with Monroe. The Madison cabinet, other than Monroe was full of incompetents. He did not appoint a landmark chief justice. Jackson and Harrison were his most effective generals in the war. His vice presidents are almost not a part of the story. Perhaps Dolley Madison herself would be the most interesting character in the Madison story that didn’t also reach the presidency.

Ranking

The latest Sienna poll rates James Madison as the 7th best president overall. He is most highly rated for his intelligence (3rd), his background (4th), his imagination (6th) and ability to compromise (6th), and his court appointments (6th). His biggest weaknesses were identified to be his foreign policy accomplishments (19th), leadership ability (17th), his luck (16th), and his willingness to take risks (15th). Executive ability was ranked 13th.

I would agree that these first two attributes are descriptive of Madison. Insofar as his intelligence ranking is concerned, I think the only debate is whether he was the most intelligent man to hold the White House. I cannot but believe that as a political philosopher, he was every bit Jefferson’s equal and probably then some. Jefferson may have Madison overall in Jefferson’s broad range of intellectual interests and pursuits, but as a political thinker, Madison may have been unparalleled. He is highly rated in his background, with designing the US Constitution, being a congressman, and eight years as Secretary of State filling out a pretty impressive resume.

I’m not so sure about his imagination or ability to compromise, though. He was certainly bound in this thinking to his conception of what the federal government’s power was, as I’ve discussed above. Perhaps he gets points for imagining he could win a war with no practical plan? He did appoint Joseph Story to the court, but his other court appointments were few in number and unremarkable, so I’m not seeing that as a strength, either. I mean, he didn’t appoint Roger Taney, so there’s that.

As for his weaknesses, yeah, initiating the War of 1812, not a great accomplishment. Appointing a completely incompetent cabinet (except for Monroe!) and then not even listening to the cabinet, not great. It seems to me that he was pretty much a disaster from an administrative standpoint and so I would mark him even lower in his leadership ability and executive ability. I think he was extremely lucky that he didn’t have the whole war blow up in his face, actually.

I kind of reject the idea that he was a top 10 president. I think his real accomplishments came outside of his presidency and I would point there first. Without going into the dreadful presidencies that start in about 1841, I’m going to say that Madison wasn’t a tremendous president.

What I Was Looking Forward to after Reading this Book

This is pretty easy. I was becoming more and more impressed with James Monroe (can you tell?) and I really wanted to read about the fifth president of the United States.

How My Understanding Lines Up (or doesn’t) with the Presidential Podcast

I am referring of course to the Washington Post’s Presidential podcast. If you are interested in these posts, but aren’t listening to that podcast, let me suggest that you should. You can find it where you get your podcasts. A youtube link to the Madison episode is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O6zud62MXng. I like to listen to podcasts at a faster pace and at 1.5 times speed is easy to hear and understand.

Interestingly, the James Madison scholar that is interviewed in this episode points to the difficulties in today’s political climate and asserts that it is the Constitution, with all of its checks and balances that Madison put in that has led us to the point where we are today: a political system where it is very difficult to get things done. He makes the point that the Constitution was written to make a more effective government, not as some libertarian document. The founding fathers wanted a government that actually worked, even as they feared too much federal power. He also makes the point that Madison, unlike Hamilton, didn’t really understand the nature of executive power.

The podcast kind of concedes that his presidency was kind of a bust and that he was a lousy wartime president. The scholar makes the argument, though, that a president need not trample on personal liberties during wartime. Even then, though, there was little support for Madison being a great president and the podcast aligns with my thinking that he wasn’t a very good president.

Another interesting tidbit in the podcast directly contradicts a story in the book that I have related above. In the podcast, the slave who was purportedly purchased by Daniel Webster wrote a memoir and he asserts in that book that he had bought his freedom from Dolley himself and late in her life he gave her funds when she was destitute. Which is correct? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

What We Can Learn from Madison’s Presidency

Madison possessed certain characteristics that don’t really play well in the modern presidency. He was an intellectual, he saw issues as complex and he wasn’t a real decisive president. The podcast makes a lot of comparisons between Madison and Obama. As someone who is generally supportive of the Obama presidency, I was frustrated with his sometimes less than certainty that Obama would have in public. I get that he was considering complex issues, I just wished that he would contain those contemplations outside of his public pronouncements. I’m not saying that discussing complex issues in public is, in a vacuum, a bad thing to do. I’m saying that Americans don’t have the appetite for it. Put it in your memoirs.

SBG’s Presidential Biography Tour: Thomas Jefferson, 3rd President of the United States

Welcome to the third installation of my journey through the presidency via presidential biographies. Today, we discuss Thomas Jefferson, historically one of the most highly regarded presidents in U.S. History and the author of the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson’s presidency has come under scrutiny in the 21st Century and at various times throughout the nation's history. In some quarters, he is held up as a bastion of freedom, whereas in other quarters, he’s seen much less positively, as a slaver who was an underhanded dealer in the political arena. As far as I’m concerned, it is hard to doubt that Jefferson was highly influential in his time and for maybe 50 years beyond, but I'm not so sure that his influence extends into the present day. To state it bluntly: Jefferson was an 18th Century man and 18th Century thinking doesn’t really hold up in modern day America. More specifically, if his idea of what the federal government should be prevailed to this day, the United States would be a collection of weak individual states, unable to capitalize on its vast collective potential. As president, though, Jefferson acted with a philosophy more in line with Federalist conceptions of what the president should be. To the extent, then that his influence does hold up, it is more in what he did, rather than what he said.

Before I go on, I am coming to the realization that reading one book on each president is, as a project, an interesting way to dip one’s toe into U.S. History. However, I’m finding that it causes me to ask more questions than it answers. In addition, I believe that I have erred by not writing down all of my thoughts before I plowed through eight books. I was reading that fast to accomplish the goal in one year. That’s like taking a road trip through every one of the 48 states in 100 hours. Sure, it can be done, but at the end, what have you accomplished? You’ve sat in a car for 100 hours. For me to expend all this effort and not document my thoughts seems like a waste. What I need to do is to get three or four of these writeups in the can and then plow forward. But here I am on Sunday morning (as I write this), not having done that. Ugh. This next couple of weeks I’m going to try and get all the rest of my completed books written up and then continue the project. I may not get done in one year, but so be it.

Of the eight presidents that I have read about to date, Jefferson is the one that I have revised my opinion downward the most. There are good things about Jefferson, but his actions during the Washington and Adams presidencies were unbelievable in modern light. I think he had middling success as president and his largest accomplishment (admittedly a huge accomplishment) was basically a gift handed to him on a silver platter.

Background

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743 and he died on July 4, 1826, the same day as John Adams. He served as the third president of the United States from March 4, 1801 to March 4, 1809, having won the 1800 and 1804 presidential elections. Jefferson, along with James Madison, were instrumental in founding the Democratic-Republican party and the D-R’s controlled the White House from 1801 though 1829, an astounding run of seven terms (although John Quincy Adams was not too much of a partisan and he was basically a man of No Party). Jefferson’s Vice President during his first term was the infamous Aaron Burr. Burr was replaced in the 1804 election by George Clinton, who served as the fourth Vice President.

Like Adams and Washington before him, Jefferson had an unbelievable career outside of his presidency. He was a delegate to the Continental Congress and was the primary author of the Declaration of Independence. He served as a diplomat in France, replacing Benjamin Franklin as the Minister to France. He was the first Secretary of State and second Vice President. He is also credited with founding the University of Virginia. Unlike his immediate predecessor Adams, Jefferson’s presidency is considered to be a successful one and he launched a political movement that held power for almost three decades. Part of why Jefferson was successful, in my view, was that he was incredibly lucky to have had the Louisiana Purchase essentially fall into his lap and because as president, he was much more practical (i.e., he abandoned his high falutin’ principles once he held the office) than he was prior to his presidency. To put a finer point on it, Jefferson and his two successors consolidated power by implementing some of their political opponent’s policies and philosophies.

What I knew About Jefferson before Reading this Book

I went to grade school, so I knew that Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence and that he was president when the Louisiana Purchase was consummated. I have been to Monticello and learned facts about Jefferson while at the site, including that he sold his books to the Library of Congress. I was aware of the Sally Hemmings situation, his time in France, and a variety of other facts about him. Before I started this project, I would say that that I knew as much about Jefferson as any president who served before my lifetime, save Washington.

I toured Monticello on the day after I toured Mount Vernon. I would have stayed there for hours longer than I did, but it was kind of rainy that day and my wife and then much younger daughter were not so keen to wander around in the rain. What jumps out when you are there is how much different it is from Mount Vernon. Mount Vernon was of a much larger scale, but the house, while much bigger than Monticello evokes a lifestyle that is much simpler and an owner that is much less sophisticated than Jefferson. The Washington kitchen was simple, food was cooked over an open hearth. Jefferson, by contrast, had a kitchen that was much more sophisticated. He (or rather, his slaves) used charcoal in his kitchen with individual masonry stoves (seen on the left) and a beautiful space.

He had a wine cellar directly below his dining room. This youtube video shows a little bit about that.

Like Mount Vernon, the kitchen was not part of the main house, but Jefferson had tucked it into the side of the hill and beneath the house, with a dumb waiter that would food to be lifted into the dining room. The entire house is one of sophistication. The grounds were magnificent and I would have loved to seen more of it. You can take a virtual tour of Monticello here.

This youtube video shows what a tour is like. It’s not the greatest video ever, but it does show how beautiful the house is. At about 4:10, you can see how he had outbuildings built into the hill. At about 6:30, you can see the wine cellar and the delivery mechanism to deliver wine up to the dining room. The kitchen is at 10:20 (briefly). The gravesite is at 11:45.

If you are interested, there is a long video here about the kitchen that was built in 1809.

The tour is well worth it if you are in the area. You can get an appreciation for how interesting Jefferson was and also, how much work his slaves did for him. I also include this information because I want it to be clear that even though, like Washington, he exploited slaves to achieve his ends, his vision about what his plantation should look like and function was pretty remarkable compared to Washington. The man was brilliant, he had great ideas and if you set aside (which you can't) the idea that he was exploiting human beings to achieve these ends, you can marvel at his thinking.

The Experience of Reading Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power

For my book on Jefferson, I selected Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power by Jon Meacham. I’ve mentioned at the site that this book, which is highly regarded (and I will say that the author is generally aligned with my political point of view), is really dissonant having read Chernow and McCullough and their perspectives on Jefferson. And, indeed, I have come to realize that Meacham himself admits that he had their books in mind when he wrote his. Here’s Meacham, discussing his book with Hugh Hewitt:

For my book on Jefferson, I selected Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power by Jon Meacham. I’ve mentioned at the site that this book, which is highly regarded (and I will say that the author is generally aligned with my political point of view), is really dissonant having read Chernow and McCullough and their perspectives on Jefferson. And, indeed, I have come to realize that Meacham himself admits that he had their books in mind when he wrote his. Here’s Meacham, discussing his book with Hugh Hewitt:

You know, Jefferson’s had a rough about 50 years, 40 years, as Hamiltonianism sort of became more respectable after Eisenhower ratified the New Deal in many ways. You know, we have arguments about big government and small government, but it’s really a matter of degree not of kind, as you know. And so Jefferson has had a rough time. Part of it, also, is that there have been so many wonderful books where Jefferson comes off badly. So whether it’s David McCullough or Ron Chernow, and I just thought that someone needs to step in and make at least a modest brief for the old boy.

I find this to be an amazing admission. Basically, he’s saying that as the New Deal gained broad acceptance in the United States, thereby discrediting Jefferson’s archaic views, it was necessary for him to rehabilitate Jefferson. Oh boy. I also find it very interesting that FDR himself claimed Jefferson as an ideological forefather of the New Deal. Really? Jefferson would have supported a payroll tax to fund a pension fund for the general population? I find that... hard to believe. In addition, I've read enough to know that save for JQA, the presidents of the Jefferson era were adamantly opposed to the federal government spending on "internal improvements" such as roads. I am perplexed by the whole connection of Jefferson to the New Deal.

Indeed, we see Meacham paint Jefferson as some sort of defender of republicanism against the tyrannical George Washington(?). As Secretary of State, he urged the tired Washington to run for a second term even as he was secretly undermining Washington by supplying stories to the press and employing, as a translator in the State Department, the publisher of one of the anti-Washington publications, an act that would have Jefferson run out of the cabinet, had it occurred in pre-Trumpian modern times. He and his boy Madison howled at Washington for the decisions that he made as the very first president of a country living under the threat of its former colonizer, the most powerful country in the world. Meanwhile, Jefferson was an uncritical supporter of the eventually failed French Revolution, not at all worried about the Reign of Terror. Meacham makes Jefferson out to be a hero – it seems to me that Jefferson’s performance as Secretary of State was pretty scandalous.

If I had not read two fantastic books about Washington and Adams before I read this book and an encyclopedic book about Madison and a perfectly good book about Monroe after, I might have been a lot more satisfied with this book. But I did read those two books and Meacham’s book seems like exactly what it was: an argument to these books. In the old marketplace of ideas, I suppose that’s great. But, I’m buying what Chernow and McCullough have to say.

Meacham also misses opportunities to humanize Jefferson that other authors have taken. McCullough (who started writing a book about both Adams and Jefferson, but settled on a book about Adams when he realized what an interesting story he had to tell) spends a good deal of time talking about the relationship between Adams and Jefferson, especially in their post presidential life. Meacham largely ignores this. In McCullough’s book you can see old Adams reinvigorated by this communication (over 150 letters exchanged) and I smiled when he mentions Adams trying to argue his case with Jefferson. Meacham gives little mention of this. I wanted to get a perspective on what Jefferson wrote. I’ll have to look elsewhere (and incidentally, you can find a complete copy of these letters collected into a book at Amazon).

As another example, there was an incident where students at the newly founded University of Virginia rioted as a protest against European instructors (which Jefferson and Madison had selected). Meacham gives us about one sentence on Jefferson’s reaction, basically, that he was disappointed. In the book I read on Madison, Ralph Ketcham (and damn, this an exhaustive book) gives us ten pages. Included in that story is a meeting where three former presidents go to Charlottesville to meet with the students (Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe). Ketcham writes that Jefferson was so distraught about the situation that he was in tears. In fact, Ketcham clearly outpaces Meacham in his discussion of the founding, including how the site of the university was chosen, the curriculum, etc. Part of that was in service to Madison’s contribution, but he clearly indicates that Jefferson’s contribution was far greater (even though Madison, who was younger than Jefferson and lived for ten years after Jefferson died and was involved with the university for a longer period of time).

I get it, the man lived 83 years and did a ton. There’s only so much you can stick in one book. But, Meacham, I feel, is writing pop culture history with an agenda of responding to what he perceives as an attack on the president. It’s not like this book was loooong. It certainly could have been another 100-200 pages and would have been completely readable. You want to exclude details about the University of Virginia? Fine. It wasn’t like that was important to Jefferson. It only made it onto his tombstone, whereas the fact that he was president of the United States did not.

One thing that Meacham did do, though, was accept as fact that Jefferson had a sexual relationship with Sally Hemmings and fathered her children. I found that interesting and, of course, this is an enormous black mark on Jefferson. Hemmings was likely his dead wife’s half sister because her father likely raped Sally’s mother. By extension, then, Jefferson was raping his wife’s sister, who was his slave, and he was enslaving his own children. Oof.

Jill Abramson writing in a book review in The New York Times states that Meacham's books are "well researched, drawing on new anecdotal material and up-to-date historiographical interpretations" and presents his "subjects as figures of heroic grandeur despite all-too-human shortcomings". I’m not too sure about the first part, but I’m definitely sure about that last part and I don’t think it’s a compliment. Of the books that I read about the first six presidents, I enjoyed this one the least.

Jefferson’s Life Before Presidency

Jefferson attended William and Mary college and then studied for the law and became a lawyer. He was a member of the House of Burgesses, the colonial legislature of Virginia from 1769-75. He was a member of the Continental Congress and, at John Adams’ urging, authored the Declaration. Jefferson was the governor of Virginia form 1779-80. When Benedict Arnold invaded Virginia, he fled the capital and was pursued unsuccessfully by Cornwallis’s men. There was some controversy about his actions in fleeing, but he was exonerated in a subsequent investigation.

After the war, Jefferson was named minister to France, where he joined Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, who were already there. John Quincy Adams was a frequent guest of Jefferson while he was in Paris and Jefferson was somewhat of a mentor for JQ. JQ would subsequently become a backer of Jefferson and one of President Jefferson’s diplomats. It was in France when Jefferson, then in his mid-30s, apparently began his sexual relationship with the 16 year old Hemmings.

Returning from France, he was confirmed as the first Secretary of State under Washington. It was in this role that Jefferson began to make his mark on the United States and the political scene. The president’s cabinet in those days was small – there were only Treasury, State, War, and Attorney General positions. Washington had Alexander Hamilton and Jefferson in his cabinet, and they laid out competing philosophies as to how the United Stats should operate. Hamilton was the proponent of a strong federal government that held debt and had significant power. Jefferson was a states’ rights guy and he felt that the states should handle their own debt. If you are struggling to manage your debts, take the help of reliable lawyers like the New Bern bankruptcy lawyers who can help you file bankruptcy and protect your assets. First of all, I think Hamilton was right when it came to monetary policy generally. Second, Washington agreed with Hamilton. Jefferson, though, was opposed and worked to sway public opinion through the press by, as mentioned above and in the Adams book, employing an employee in the State department in a bogus job as an incentive to draw him to Philadelphia and publish a newspaper critical of the administration for which Jefferson worked.

Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State in late 1793 and returned home. He opposed the Jay Treaty, which Washington signed, feeling that the treaty undermined the government. In fact, the Jay Treaty was controversial, and Washington was not pleased with it, but he signed it nevertheless. Jefferson would find out later that as president that is not so easy to make certain decisions. Jefferson ran for president in 1796 and came in second to Adams, meaning that he was now the second Vice President of the United States due to a weakness in the Constitution. This weakness would rise up again in 1800, leading to the adoption of the 12th Amendment.

To say that Jefferson was disloyal to Adams as vice president is an understatement. As we discussed in the Adams post, Jefferson actively undermined the president during the XYZ affair, telling the French counsel in secret talks not stall out negotiations between France and the US because Adams would be a one term president. In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts – not Adams’s best move by a long shot – Jefferson – as vice president !!!! – authored (anonymously of course, because he was a chicken shit) the Kentucky Resolution, which advocated for nullification, a noxious notion that Chernow believes led in part to the Civil War. Washington felt that if these policies were pursued, it could lead to disunion. For my part, I think of Jefferson (and Madison assisted in this effort by writing a similar Virginia Resolution) advocating for this as the epitome of his complete lack of understanding as to what was important for American as a country to thrive and grow as a united country. The remnants of this bullshit continue to this day in some quarters, so here lies some influence from Jefferson: he inspired some of the nullification nonsense still pervading from some quarters.

Jefferson ran against Adams in 1800 and he beat Adams, largely because his mortal enemy, Hamilton broke with Adams prior to the election. Adams came in third behind Jefferson and Burr, who tied, throwing the election into the Federalist controlled House of Representatives. Burr, whose own underhandedness made Jefferson a paragon of virtue by comparison, was unwilling to step aside and let Jefferson win the election in the House of Representatives. After 36 votes, Jefferson prevailed by a single vote, due in part to Hamilton’s lobbying for Jefferson and maybe a little quid pro quo on Jefferson’s part (did he promise some appointments in exchange for that vote? Was this a foreshadowing of the 1824 election? The world may never now). Jefferson nominated James Madison as his secretary of state. Madison, his closest ally during his days before the presidency would retain that role for another eight years.

Key Challenges/Features of Jefferson’s Presidency

There were two big issues that I want to discuss about Jefferson’s presidency: his acquisition of Louisiana and his dealing with the ongoing threat from England. Before I get there, though, I want to discuss a couple of other things: how Jefferson viewed accessibility to the White House itself and his treatment of some of Adams’s initiatives.

Jefferson very much bought into a simple, republican ideal in terms of how the president should present himself. He did not want to project himself as some sort of king and he didn’t dress formally on a day-to-day basis. In that regard, he had a very 2020 work from home ethic. He was not above working in slippers or even greeting people in the White House in that type of attire, even when meeting representatives from other countries. Whereas Adams was concerned with making a good impression to the world via the presentation of the presidential mansion, Jefferson did not seem to care (or he was making a very deliberate departure from that of Adams and Washington). Frankly, I don’t get where he was going with that, but whatever. (Note: the podcast indicates that he did this on purpose to send a message to representatives of other countries. I'm still not sure I understand what he was trying to accomplish.)

The other thing was that Jefferson very consciously made a clean break with Adams policy wise in some key areas. I mentioned in the Adams post how the president had enacted a law to expand the courts and pack them with Federalists. Jefferson, having congressional majorities behind him, repealed the so-called Midnight Judges act. He also reduced the size of the navy that Adams built up. (Note that Adams kept Washington’s cabinet, a pretty big mistake.) I am pretty sure that I agree with the idea of being able to undo what your predecessor did if you don’t agree (and boy howdy, do we see that in the US these days). However, Jefferson’s reduction of the naval ships was a flat out boneheaded move. Hey, I’m not a guy that loves an endless build up of military force. But, understand that the US economy relied on the ability to protect its shipping. England, in those days, would accost U.S. ships and search for British sailors that had left the British navy and went to work on US ships (because being in the British navy sucked). They called this “impressment” and if some US citizens were kidnapped off of the ships and forced to serve in the British navy, well so what. Weakening the navy in view of such aggression served no good purpose for the United States.

Louisiana Purchase

It seems impossible to me that any middle schooler in the United States does not know (unless they flat out aren’t paying attention at all) that Jefferson was president when the U.S. completed the Louisiana Purchase from France. From what I understood, the US bought Louisiana as it was understood to be from France for $15 million an absolute bargain. I knew so very little about this monumental event prior to starting my starting this process that it’s almost embarrassing. First of all, I just had this vague notion of what France was in 1803, never really understanding that the U.S. bought Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte. Thus, I further did not understand that Napoleon had designs on establishing a large presence in North America via Louisiana but was diverted from that plan when his troops were unable to put down an insurrection in what is now Haiti. (I mentioned in my post about Adams how Yellow Fever ravaged the city of Philadelphia and how Yellow Fever was brought to the United States via slave trading ships.) It turns out that the French Army was devastated in Haiti because of Yellow Fever (the locals were not as devastated because a lot of them had already had it, and survival ensured lifetime immunity) and lost all but 5,000 of 20,000 troops in that campaign. That, coupled with Napoleon’s (mis)adventures in Europe, caused Napoleon to decide to cut bait. I’m sure that getting $15 million to finance his European wars was really the ultimate incentive.

Jefferson sent James Monroe to France to try and purchase New Orleans (this was very important because the United States wanted control of the Mississippi River). It became quickly apparent that France wanted to sell their entire interest in North America and for a pittance, really. To their credit, Monroe and later, Jefferson, did not look a gift horse in the mouth. Jefferson’s position, though, was that under the Constitution, the federal government did not have the power to purchase land without an amendment. Of course, Jefferson, in the interest of expediency, authorized this purchase and expanded the power of the presidency through this precedent. One wonders, though, if Jefferson was willing to buy New Orleans, was of the mind that this would require an Amendment? If so, why wasn’t he pushing for an Amendment as part of his plan? Was he going to wait until the sale was agreed to? Seems like a not well thought out plan. Here’s another really interesting tidbit: the exact parameters of what the US actually bought was not defined in the sale. There was some sort of agreement that the parties would figure that out later (!!!!!!). Andrew Jackson asserted that the sale included Florida. That’s, I think, ridiculous, but as we will find out later, this wasn’t the only ridiculous position that Jackson took on such matters. What we really bought in this sale was France out of NA. That was a huge deal for the westward expansion of the United States and it would set up enormous issues for the country in terms of slavery expansion and the removal of native peoples from areas east of the Mississippi.

What’s truly delicious about this entire episode is that the Louisiana Purchase is that in retrospect it is the thing that defines Jefferson’s presidency but to accomplish it, he had to abandon his small government principles. I would imagine that if Washington or Adams had pulled off this deal, he would. Have. Been. OUTRAGED! Turns out that when you sit in the big chair, things look different. I think he did the right thing… eliminating France as a threat was a good thing. But, again, and I do want to put a very fine point on this: Jefferson’s whole philosophy of what the federal government should be was incompatible with the best interests of the country.

Embargo Act

As I mentioned above, the accosting of U.S. ships was a problem, so much so that the threat of war with England loomed over part of the Jefferson presidency. In response, Jefferson sent James Monroe over to England to try and get a treaty to stop this practice (along with a myriad of other issues). Monroe was able to deliver a treaty signed by England, but that treaty did not deal with the impressment issue. As an aside, I should note here that I think Monroe deserves a lot more credit than he receives for his role as a founding father. This treaty, had it been approved by the senate, may not have averted the War of 1812, but the treaty to end that war basically set the terms that were drawn up in this treaty. So, huh. But the treaty wasn’t agreed to because Jefferson refused to send it to the senate for ratification.

In 1807, there were some hostilities with British ships firing on some American ships. Jefferson prepared for war, ordering the purchase of wartime supplies (arms and ammunition) and he wrote that the “laws of necessity, of self-preservation, of saving our country when in danger, are of higher obligation” than observing the laws. Again, huh. Here is Jefferson, in violation of his principles, acting to prepare the country in a time of trouble. I think he’s partly to blame for the increased hostilities (he prevented the treaty from being ratified), but it is also possible that England would have continued their impressment regardless. Given the position that he was in, he was probably correct to prepare for increased hostilities. But again, we see how Jefferson’s concepts of what the federal government should be colliding with the reality on the ground and losing. On the one hand, good, he adapted. On the other hand, he was a huge shithead during his time as Secretary of State and Vice President.

His response also included the passage of the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited trade with foreign nations. Jefferson understood, correctly, that the United States did not want to get drawn into the Napoleonic Wars and that as country, we should remain neutral if for no other reason that we were not strong enough to get involved on one side or the other. However, the embargo was a total failure and only hurt the US economy. There was significant resistance to the embargo in the Eastern states (i.e., New England), who were the most affected by the law. In addition, there is no evidence that it reduced any tensions with England, in fact, it probably hastened the onset of war, which would happen three years after Jefferson left office. Plus, there’s this: as Meacham said, the act was a projection of power that surpassed the Alien and Sedition Acts and others have said it was the type of power that Jefferson himself used as justification in the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson’s Post-Presidency

After his presidency, he retired to Monticello and pursued various interests. He founded the University of Virginia (this included designing the buildings on the campus, planning the curriculum, and serving as the first rector for a year). Jefferson was a believer in public education, free from religious influences.

When Washington was sacked in 1814 by the British (in a war he helped precipitate, I think), he sold his library of about 6000 books to the library of Congress for about 25,000 (used that to pay off debts). He began amassing another library, which he eventually donated to UVa.

He attempted to write an autobiography but did not finish (if he knew how much one of those fetches these days, he might have finished).

In a sad commentary on his life, Jefferson proposed what amounted to a raffle for his Monticello property. Meacham only notes that it failed. Apparently, Monticello was valued at $71,000 and he wanted to sell over 11,000 tickets at $10 apiece. Sales of the tickets were good at first, but after Jefferson died, people apparently did not want to support Jefferson’s heirs, and the sales stalled out at just over 1,000 tickets. A couple of years after the raffle was proposed, it was canceled (I’m assuming the money was returned). His sole remaining daughter sold Monticello and his 100+ slaves. Sally Hemmings and her children were not sold, but Hemmings was allowed to live as a free woman in Charlottesville. (It is assumed that Hemmings was 3/4 white – her mother also being the product of a slave master raping his slave – and her children then were 7/8 white and they were apparently able to pass as white.)

Jefferson’s Family Life

Jefferson was born the son of an uneducated planter who wanted his son to have an education. He attended the College of William and Mary, where he apparently partied too much as a freshman (surprise!) and buckled down after that. He later became a lawyer and shortly thereafter, he was a legislator in the House of Burgesses (from 1769-75) and as a lawyer represented slaves in some cases. He married his 3rd cousin, Martha (who like Martha Washington, was a young widow) on New Year’s Day 1772, she bore him six children, only two of whom survived to adulthood and only one of whom outlived him. Her father died in 1773 and Jefferson and his wife were bequeathed 135 slaves (including Sally Hemmings). Martha died in 1782 and asked him never to remarry because she couldn’t bear the thought of another mother raising her children (she herself had a stepmother). He honored that request, although…. Dolley Madison acted as hostess during most of his presidency before being first lady for eight years immediately after Jefferson’s presidency.

His one daughter who lived past her twenties, Martha, lived at Monticello with Jefferson after his retirement along with her husband and 11 children. She cared for him for the rest of his life. She and Jefferson were very close.

Thomas Jefferson: The Man

As a politician, Jefferson appears to have been underhanded, a back stabber, and someone who cast aside his principles in favor of expediency. Unlike Adams, who was fearless in his advocacy for his positions, right or wrong, Jefferson often stood back and advanced his positions through secretive measures. These are… not great characteristics.

On a personal level, he was completely incapable of managing his own finances, showing a remarkable lack of restraint that would eventually leave his personal estate in ruins. He was given latitude by his bill collectors – he was Thomas Jefferson, after all, but he would have been well advised not to buy every godamned thing that tickled his fancy. In all of the first three books that I read, Jefferson’s spending was highlighted. It was bad enough that his personal fortune was acquired off of the backs of the slaves that he owned, he further compounded the situation by pissing all of it away, an enormous personal weakness.

He was certainly shameful in his behavior regarding his wife's likely half-sister Hemmings. Jefferson was a young widower to be sure and it seems only fair that a man of his young age, left alone by the untimely early death of his beloved wife, could and probably should have found another mate. It’s not like Jefferson couldn’t have found another woman to marry, he was probably the most eligible bachelor in the country. He chose, however, to make a slave his concubine, to impregnate her repeatedly, and to enslave his own children. The best thing one can say about this is that Jefferson’s despicable behavior wasn’t that far out of the norm in those days.

Jefferson was, however, an intelligent man, a curious man, and a man who cared about education and the freedom of religion. His founding of the University of Virginia was of great credit to him. His brilliant authorship of the Declaration of Independence showed his ability to express his thoughts brilliantly. I think it is fair to say that he was a remarkable man and a great influence in his age. But his negative traits land him as the least admirable man of the first six men who held the presidency, by far.

Jefferson’s America

By the time that Jefferson took office, the Democratic-Republican party was becoming the very dominant party in the United States and would become that in a way that no other party has ever had control before or since. The Federalist party was doomed to a regional party in the northeast, and was a mostly reactionary party. The United States of the early 19th Century was beginning a period of one party rule for about 25 years. The country was already beginning to flex its muscles westward and Jefferson was beginning the policy of Indian removal into areas west of the Mississippi River. In the northwest, William Henry Harrison, Mr. Jefferson’s Hammer, the first governor of the Indiana Territory, was aggressively acquiring Indian land through a series of treaties and various military actions.

Factions were beginning to form between the north and the south, but slavery was not quite yet the dominant issue between these regions. Politicians would eventually evolve into the assertion that slavery was a positive good, but this wasn’t quite evident in Jefferson’s time.

What Really Surprised Me

Although not covered in the Meacham book extensively, I cannot believe that I did not know the circumstances that led to the Louisiana Purchase. It is true that Jefferson sent James Monroe to France to purchase the city of New Orleans, but it turned out that France was willing to just hand it over was stunning. I was also surprised to learn that Jefferson had commissioned Lewis and Clark to do their exploration before the Louisiana Purchase.

What one person (not a president) would I want to read about from Jefferson’s era as President?

I’m not sure that I can point to that person. The key players in this story, at least as far as I’m concerned, were Madison and, to a lesser extent, Monroe. Perhaps, I might say Lafayette or even the French Revolution (which is not a person), but really the answer here is no one person. Actually, the person I want to read more about is Jefferson himself.

Ranking

The latest Sienna poll rates Jefferson as the 5th best president of all time. The poll rates him as the most intelligent president and a top ten president in all of its categories, except for integrity, ability to compromise (both 14th) and handling of the US Economy (20th). I’m going to say this: my impression is that his Secretary of State, James Madison, was more intelligent than he was and that Madison was a tremendous driving force behind a lot of what Jefferson did, from his early opposition to Washington, to many of his policies in the White House, and even after his time in the White House, Madison was there to support Jefferson. Not that that is a bad thing – a good president needs good people around him that he can trust and upon which he can rely. I think that Jefferson’s handling of the tensions with England and his resulting economic policies look pretty bad in retrospect (and were highly criticized at the time). I also think that he gets more credit for accepting the gift of the Louisiana Purchase than he should have. In addition, I think that Jefferson’s integrity is rated too high. He was a rapist who enslaved his own children, he spent like a drunken fool, and he surreptitiously undermined the president that he served as Secretary of State. None of those things were done in his capacity as president, though, so maybe 14th is okay (just ignore how he dealt with the Louisiana Purchase) ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Frankly, I don’t see this ranking. This has to be a direct result of his successful Louisiana Purchase, which was a monumental benefit to the nation. But what president would not have accepted this gift? When I read about his bungling of the English situation – and maybe I’m being too tough here, there weren’t real good options, does his record scream top five presidents? I would suggest that avoiding a war with Britain should have been job one of his second term and his attempts to do so failed.

What I Was Looking Forward to after Reading this Book

Clearly, given the close association between Jefferson and Madison and given some of my disappointment with this book as to the depth of this book (i.e., the cursory treatment of certain topics in the book), I was looking to get more insight about Jefferson vis-à-vis the Madison book. As superficial as this book was, the Madison book was a deep dive into Madison and I did in fact find more about Jefferson in that book.

But it must be said that what I really want to know about more than anything is more about Jefferson and his presidency. The picture I have is a guy who avoided direct conflict and worked behind the scenes through others to advocate for his positions. However, when in the actual seat of power, he found that his ideals weren’t as workable as he might have thought.

How My Understanding Lines Up (or doesn’t) with the Presidential Podcast

I am referring of course to the Washington Post’s Presidential podcast.

Jon Meacham was a guest on this episode and, surprisingly, he wasn’t projecting as positive a view as he did in his book and that was consistent with all of the guests (there were several) in the podcast. This particular episode of the podcast was excellent and really left you the inescapable conclusion that I’ve drawn here: namely that Jefferson was a man of great talent and intellect who made great contributions (the Declaration and the Purchase), but that his personal weaknesses and his behavior during the Washington presidency was troubling indeed. Plus, there is the matter of slavery and Hemmings.

One of the guests on the podcasts goes so far as to suggest that if Jefferson had taken a stronger position against slavery that he might have been able to prevent slavery from becoming the overwhelming problem that it eventually became. The inference here was that Jefferson, with his monumental influence in the first third of the century, could have grabbed this moment to change the trajectory of slavery in the US, but he did not do so. They also pointed out that he had over 600 slaves in his lifetime and freed none of them. By contrast, Washington freed all his slaves (in his will) and gave them land. The difference is stark. They also indicated that he would punish slaves by selling them off and splitting up families. He believed that enslaved people could not feel love like white people could, according to the podcast. That is an amazingly awful revelation. They also pointed out that the population of freed black people rose dramatically at the end of Jefferson's life because other Virginians were willing to free their slaves. Jefferson did not participate in this activity, partly because he had frittered away so much money that he could not afford to do so. There is also kind of a parallel drawn between Jefferson and America as a whole. The confounding contradictions in a man who could proclaim all men are created equal and believe what he believed about his slaves kind of mirrors America as a whole.

What Can We Learn from Jefferson’s Presidency

I would argue that the true lesson of the Jefferson presidency is the overriding importance of the presidency in American government. Ever since the founding, the power of the presidency has increased steadily, for good or for bad. It is understandable that the founding fathers wanted a limited executive branch given that they broke free from a monarchy. I think its also true that checks on that power have been, are now, and always will be necessary. My thinking right now is that Jefferson proved the need/danger of great executive power. It’s almost a Nixon goes to China moment. Jefferson, the great republican and believer in limited federal power, Jefferson himself expanded the presidential role in a way that he would have forcefully objected to just a few years before he did it.

SBG’s Presidential Tour: John Adams, 2nd President of the United States

Welcome to my discussion of the second president of the United States, John Adams. I’m still on the ninth book in this series (I didn’t read much this week). I think that I want to remain several books ahead of the story that I’m publishing in a given week, because I’ve found that knowing what’s coming helps add perspective to the story of the week. This is conflicting with the idea that I want to write these stories as soon as possible after I’ve read the book. My plan is to put down my thoughts as I’m reading now. Books three through eight will suffer a little because I’m just going to forget a lot about what I’ve read by the time I get to the write up.