№ 4

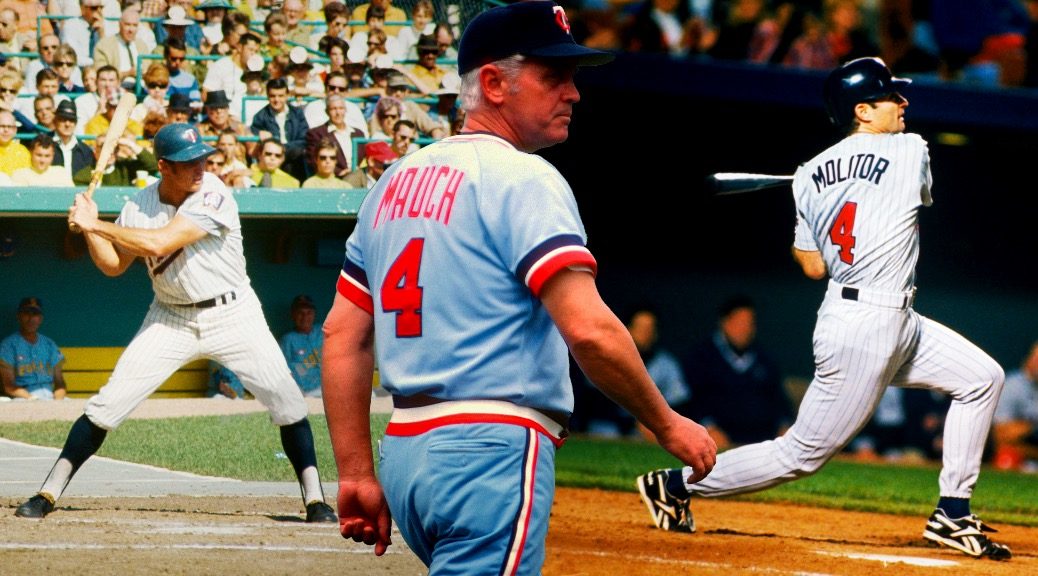

Worn by: Bob Allison, 1961–70; Steve Braun, 1971–75; Gene Mauch, 1976–80 (as manager); Mark Funderburk, 1981; Jim Eisenreich, 1982–84; Chris Speier, 1984; Steve Lombardozzi, 1985–88; Orlando Mercado, 1989; Chip Hale, 1990–95; Paul Molitor, 1996–98, (2000–01, 2003, 2014 (as coach), 2015–18 (as manager)); Augie Ojeda, 2004

Incumbent: none

Highest rWAR: Allison, 30.5

Lowest rWAR: Funderburk, -0.4

Best season: Allison, 7.4 rWAR (1963)

Worst season: Funderburk (1981), Eisenreich (1984), & Hale (1989), -0.4

Bob Allison

Bob Allison was headed into his third full MLB season when the Senators moved to Minnesota. He was already a very exciting player, with an athletic . In 1959, Allison hit 30 homers and a led the American League with 9 triples as Washington's primary center fielder. (His defense in center left something to be desired; his glove rated -12 Fielding Runs that year, so despite his 122 OPS+, he was merely a 1.4 rWAR player). As with Zoilo Versalles, Allison changed numbers after the move, leaving Nº 26 behind and donning Nº 4 in Minnesota. Once here, he became a potent middle-of-the order threat for the Twins during their greatest period of sustained success. Allison most frequently hit 5th, 4th, or 6th in the order. His best season came in 1963, when the Twins finished 91-70, in third despite a Pythag 98-63 that would've tied them with the second-place White Sox. Allison finished 15th in MVP voting but was the best player in the American League by rWAR.

That season came during a four-year peak, 1962–1965, that saw Allison average 5.7 rWAR while playing three different primary positions: first right field, then first base, and finally left field. Sam Mele's decision to play Harmon Killebrew in left field for 157 games and Allison at first for 93 is puzzling. Vic Power had been the Twins' primary at first in '62 and '63, but he only got 7 starts in 19 total games and was sent to the Angels in a three-way June '64 trade that brought Jerry Kindall to Minnesota. Harmon had been playing left field for two years, but had been the primary first baseman in 1961, and was the primary first baseman through mid-June 1965. Allison moved back to the outfield in '65, shifting to left to make room for Tony O.

Allison struggled through injuries from the mid-Sixties through his retirement in 1970. He suffered four wrist injuries, including two fractures from HBPs. Knee trouble necessitated cortisone shots to stay on the field. And, of course, he was a victim in one of the most infamous incidents in Twins history: on a swing through Detroit in 1969, Allison was KO'd by Dave Boswell, who had gotten into it with Art Fowler and Billy Martin. Considering the wrist injuries, Allison's production at the plate was beyond reproach while he remained a regular, including resurgent seasons at 32 (134 OPS+) and 33 (129 OPS+). He dropped off from there, down to a 106 OPS+ in 220 PA in 1969, and then to a 83 OPS+ in 1970. Even in that last season, he could be dangerous at the plate: his batting line as a pinch hitter that year was .300/.391/.550 (23 PA). When he retired, Bob Allison had hit the second most home runs in Twins and Senators franchise history by a pretty wide margin. (He passed Roy Sievers in 1965.) Bob Allison's 211 homers with the Twins have only been surpassed by four Twins since he hung up his spikes. By traditional stats, he was all over the franchise leaderboard: 7th in RBI, 5th in walks, 2nd in strikeouts, 6th in extra-base hits, and 7th in total bases. He was also third among position players in WPA, 9th in rWAR, and first all-time in Power/Speed Number (which might have been the first quasi-sabermetric stat to draw my interest), though none of these things were known at the time of his retirement.

Steve Braun

We've already encountered Steve Braun once in this series, and now is the time to dwell on him for a moment. The Twins traded Graig Nettles after the 1969 season. Ostensibly, Nettles was blocked by Harmon Killebrew, who was named the AL MVP, but was also turning 34 on legs that were susceptible to injury. Harmon played one more season at third, then moved across the diamond to first. Braun succeeded him. It would be unfair to Braun to compare him to Nettles; after all, he didn't make the trade — Calvin Griffith did. So, on to Braun's story.

Braun played his first six seasons with the Twins, earning almost all of his career rWAR in those years. (He played until 1985.) He didn't hit for power (.097 ISO), and he was a so-so fielder — some years pretty good, some years not according to Fielding Runs. What he excelled at, however, was getting on base. Braun had a .376 OBP with the Twins, which buoyed his barely better than league average power sufficiently to record a 116 OPS+ during his Twins tenure. Numbers broken out for his Twins years are just onerous enough to obtain, but over his entire career, Braun walked 5% more often than league average and struck out 3.2% less often.

In the field, he was a bit of a nomad. While he saw most of his time at third base in his first two seasons, the Twins were able to put Braun at second and shortstop on occasion. He finally gave way at third for Eric Soderholm in 1974, moving to left field. In 1975 he started the year with nine games at first base, then moved back to left for the balance of the year. In his last year with the Twins Braun mostly served as DH, though he wasn't the primary, playing some left field and third base. The Mariners nabbed him in the 1976 Expansion draft.

Steve Braun's excellent on-base skills and utility helped him average 2.5 rWAR per season during his time with the Twins. Of his 17.4 rWAR, 15.0 came in a Twins uniform. Aaron Gleeman has long considered him a mostly forgotten, underappreciated player from Twins history, first writing about him in his Top 50 Twins series, and again in a piece for Baseball Prospectus as part of BP's introduction of their Deserved Runs Created (DRC+) stat, calling him "the most underrated non-star in Twins history."

Gene Mauch

Gene Mauch never wore Nº 4 as a player, though he did wear the number twice for the '48 Dodgers. He was Roy Smalley's brother-in-law, which meant he was Roy Smalley's uncle. We'll encounter his nephew shortly. Mauch came to managing through the light-hitting infielder unemployment program. Though Mauch was nicknamed the Little General at some point, he was the Young General first; he was only 34 when he took over the Phillies' clubhouse as the team's third manager of 1960. He managed Philadelphia for nine seasons. After a dismal first two years (.382 and .305 winning percentages!), he got the club to .500 or better every season afterward, including a run of pretty good years from '63–'66. Fired in 1968, he landed in Montreal the next season and endured a .321 year. Fortunately, that was the last time a team Mauch managed ever lost 110 games, or even 100 games. Unfortunately, Mauch's Expos never cracked .500 while he was in Quebec.

Mauch took over in Minnesota in 1976, replacing Rhu_Ru favorite Frank Quilici. In June, the Twins traded ace Bert Blyleven to the Texas Rangers for Mauch's nephew, 23 year old switch-hitting shortstop Roy Smalley. Bert seems likely to have welcomed the exit from Minnesota, if not the destination; he flipped Met Stadium fans the bird the day before he was sent to Hades Arlington Stadium. Other players and cash were involved. Smalley took a couple years to develop into, briefly, the best shortstop in the American League. Mauch's Twins did well his first two years, but slipped under .500 in 1978, then lost Rod Carew to Calvin Griffith's penurious wallet, stupidity, and prejudice. A brief surge up to .506 in 1979 was the last time the Twins would be north of break-even until 1987. Mauch's teams over this period consistently under-performed their Pythag records:

| Year | Actual W-L | Actual % | Pythag W-L | Pythag % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | 85-77 | .525 | 85-77 | .525 |

| 1977 | 84-77 | .522 | 89-72 | .551 |

| 1978 | 73-89 | .451 | 80-82 | .492 |

| 1979 | 82-80 | .506 | 85-77 | .524 |

While this was not egregious underperformance, Mauch seems like a frustrating manager, a rigid skipper bent on smallball tactics. His teams clearly had some talent, but never finished better than third while Mauch was the manager. Clearly, much of this falls on Calvin Griffith, but Mauch's increasingly shorter stays in gigs suggest he may have been a burr in more than one saddle before he ever started working for Gene Autry. I would've pegged Mauch as a hidebound traditionalist, but his New York Times obituary suggests he might not have owned that label:

A lean, silver-haired presence in the dugout, Mauch was adept at gaining an edge. He kept computer printouts to check what batters had done against certain pitchers before that kind of analysis became customary. Rod Carew, the Minnesota Twins' Hall of Famer, once recalled how Mauch deployed a five-man infield four or five times on a single road trip to cut off the winning run at home plate in the ninth inning, and how it worked every time.

Mauch left the Twins after 125 games in 1980. He caught up with Rod Carew in California, where he had some success and some bitter disappointment.

Jim Eisenreich

Jim Eisenreich was one of two native Minnesotans living their dream in 1982. Kent Hrbek played 24 games with the Twins in late 1981, and Eisenreich appeared set to follow him the next season, less than two years after being selected out of St. Cloud State in the 16th round of the draft. Apparently Eisenreich was a non-roster invitee to spring training after a .311/.407/.507 (585 PA) year with Wisconsin Rapids in 1981. Like Hrbek, he parlayed that success into a jump from Low-A ball to Minnesota. In the span of a season, the Twins graduated two 16th/17th round picks with no experience above A ball. That speaks to both the state of the major league team, but also the potential Hrbek and Eisenreich had when they arrived. For his part, Eisenreich won the starting center field gig and made his major league debut in the Metrodome on 06 April 1982. He had to wait until the next day to collect his first hit, a single off Jim Beattie that scored Gary Ward and Sal Butera. It took a few more games to get his bat going, but he carried a .300/.385/.438 line into Boston in early May.

Unfortunately, an undiagnosed neurological disorder thwarted not only his season, but his career with the Twins. Eisenreich had already pulled himself from his three previous games in Minnesota, leaving in the sixth inning once and the fifth twice. According to Eisenreich's SABR bio, an interview with Patrick Reusse for The Sporting News was followed by a piece in a Boston newspaper that ran the day the Twins got to town and fueled intense heckling from Red Sox fans. Eisenreich left the game in the fourth that day, and in the third the next. He didn't play again until 28 May, and didn't play another complete game in 1982; his season was over on 10 June, after just 34 games.

A proper diagnosis had eluded Eisenreich's doctors for well over a decade. As a child, his doctors had diagnosed him hyperactive and prescribed him Valium. Doctors at St. Mary's Hospital in Minneapolis presented three diagnoses: social phobia (now called social anxiety disorder), agoraphobia, or Tourette's syndrome. Eisenreich believed the Tourettte's diagnosis was correct; the Twins' team physician thought that was a convenient excuse and preferred a combined social phobia-agoraphobia diagnosis. From a June 1987 Sports Illustrated profile of Eisenriech:

Dr. Faruk Abuzzahab was the expert on Tourette syndrome who made that diagnosis at St. Mary's and who so informed Dr. Leonard Michienzi, the Twins' team physician. Michienzi disagreed. He supported the diagnosis that Eisenreich suffered from some combination of stage fright and agoraphobia, and his support of that diagnosis eventually led to the player's retirement from the Twins.

Today Michienzi continues to believe that diagnosis. "Jim likes the diagnosis of Tourette," says Michienzi. "It takes the burden off his family and keeps away from any stigma that psychological disorders have in our society. Maybe he is a Tourette, but I'm still not convinced he is." Michienzi insists that a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome does not explain why the violent shaking first came so severely those nights in April and May of 1982, and why it was only so intense when he stood in center-field. "I think large crowds bother him," says Michienzi. "He has double-deck syndrome."

"He's a small-town boy," says Abuzzahab. "The Twins' doctors thought the limelight and attention aggravated his condition." Abuzzahab's diagnosis has been supported by Dr. Arthur Shapiro, director of the Tourette and Tic Laboratory and Clinic of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. "If Abuzzahab diagnosed him as having Tourette," says Shapiro, "he probably has it."

Eisenreich endured a number of treatment regimens over the next two-and-a-half years. Apparently traquilizers used as anti-seizure meds were prescribed, but these prevented him from performing up to his potential on the field. Eisenreich attempted to play in 1983 (2 games) and 1984 (12 games), but his symptoms — hyperventilation, grunting, & twitching — were unrelenting. He finally asked the Twins to put him on the voluntary retired list. Misunderstood by fans and misdiagnosed & maltreated by doctors, Eisenreich did not play professionally at all in 1985 or 1986.

He continued to play centerfield for the St. Cloud Saints, though, and strong seasons helped convince him to try one more time. Eisenreich asked to be reinstated from the retired list and was told by the Twins he wouldn't be permitted to play for the team. Instead, he was placed on waivers. Kansas City claimed Eisenreich in October 1986 after a St. Cloud State teammate, now working in scouting and player development, convinced Royals GM John Schuerholz to pay $1 for his rights.

In 1987, Eisenreich began putting his career back together. It must have been difficult to watch his former team win the World Series without him (and one wonders what the '84 or '87 Twins would have been like with Eisenreich in the outfield), but he paved his own way back to the major leagues. Playing all three outfield spots, Eisenreich hit .277/.320/.390 (98 OPS+) over 2100 PA for the Royals. He signed a free agent deal with the Phillies in 1993 and reached the World Series that season. His stay in Philadelphia, which began at age 34 and ended with his age 37 season, provides the best glimpse of what Jim Eisenreich might have become, had he simply gotten proper treatment in 1982. Over four seasons and 1500 PA, Eisenreich hit .324/.381/.453 (120 OPS+) as the strong side of a platoon, first with Wes Chamberlin, then Mark Whiten. A free agent again heading into his age 38 season, he signed with the Florida Marlins to play the outfield corners and some first base. With the Marlins, Eisenreich finally won the World Series that had eluded him by exclusion in 1987 and by defeat in 1993. He closed out his career with one more season, split between the Marlins and Dodgers. To surmount what nearly wrecked his career in his early twenties and play until he was 39 suggests Jim Eisenreich is a pretty remarkable, resilient person. We can wonder what might have been, but we should dwell on what he actually did.

Steve Lombardozzi

I enjoyed saying Steve Lombardozzi's last name more than I enjoyed his play with the Twins. Second base was an offensive black hole between Tim Teufel's departure via trade and Chuck Knoblauch's arrival in 1991. Lombo was the primary there in '86, '87, and '88, and posted a 77 OPS+ and largely serviceable defense. He did have the best year of his career with the glove in '87 (10 Fielding Runs), so at least his timing was good. He's mostly remembered as either a member of the Twins' first World Championship team, Dan Gladden's punching bag, or Steve Lombardozzi's father.

Chip Hale

Chip Hale seems like the kind of prospect who would be more properly evaluated today than he was when he was in the Twins farm system, but at one point he looked like he might be a future contributor. He grew up in San Jose and played college ball at Arizona, which meant he had plenty of warm weather seasons to develop. He was drafted in the 17th round and reached the Twins in his third season. His .273/.330/.370 batting line at Portland in'89 was nothing to write home about, but he was two years younger than his league. A level ahead of Knoblauch, Hale was presumably on track for a spot on the 25-man after hitting .280/.366/.357 at Portrland in 1990. Score issued a set of 100 Rising Star cards in 1991; #39 featured Chip Hale. Though three other Twins were featured in that set, Knoblauch didn't get a card. Instead, Skippy hopped over Hale from AA Orlando to the starting second base gig in 1991. He repeated AAA for the third time in 1992, before splitting 1993 between Portland and Minnesota. In that time, he was passed not only by Knobby, but Jeff Reboulet, Terry Jorgensen, and Pat Meares. He got all of 652 PA with the Twins across six seasons, posting an 87 OPS+ with average defense at second and third base, and played a bit for the Dodgers in his last major league stint. He came close to reuniting with the Twins when he interviewed to succeed Ron Gardenhire as the Twins' manager. At the time, Hale was the Athletics' bench coach. The Twins hired the guy who wore Nº 4 after Hale, who in turn took over the Diamondbacks after Kirk Gibson and Alan Trammell were ousted from the organization. Hale didn't last long, either; he and GM Dave Stewart were fired after the 2016 season. Hale landed back in Oakland for a year, then signed on as Dave Martinez' bench coach in Washington. He filled in as interim manager when Martinez was hospitalized for cardiac treatment last September, and no doubt savored the Nationals' victory over the Astros in the World Series.

Paul Molitor

Paul Molitor's baseball roots were planted and nourished in Minnesota. Though it took him nearly twenty years to get to the the team he grew up rooting for in St. Paul, once he was back home his baseball present and future was almost always intertwined with the Twins. An all-state selection and champ in baseball and basketball, Molitor was drafted by the Cardinals the 28th round of the 1974 draft. He didn't sign and took a scholarship to play for Dick Siebert at the U of M, where he broke in as a starter at second in his first season. He became a collegiate star almost immediately, and was moved to shortstop. The Brewers took Molitor 3rd overall in the 1977 draft, and he signed. The U eventually retired his Nº 11.

Molitor got in a half-season with the Burlington Bees, the Brewers' A-level affiliate that year. With Robin Yount out until May, Molitor was suddenly the Brewers' opening day shortstop. For all that, he had a pretty good year, even if his .673 OPS didn't sparkle. Apart from a couple of rehabilitation assignments, he never went back to the minors, and the Brewers suddenly had two really good middle infielders in their early twenties. We know about the injuries, of course, and the problems with cocaine. What is often less remarked upon is the new manager Buck Rogers' decision move native son Jim Gantner from third to second, and to force Molitor to play center field in 1981, displacing Gorman Thomas to right field. Don Money took over third. It was a stupid decision; Molitor slumped to a .675 OPS (100 OPS+), Don Money wasn't very good, and Thomas apparently resented it. An ankle injury cost Molitor most of his season, though it wasn't incurred in the outfield. Rogers moved Molitor again in 1982, this time to third base, where he stayed pretty consistently until 1989.

When Molitor was fully healthy, he was one of the best players in the league, averaging 4.0 rWAR per season from 1979–1989, pretty impressive considering he lost almost all of 1984 to Tommy John surgery and averaged only 118 games per season over the same stretch. His injuries were numerous and no doubt inhibited his performance to varying degrees. Molitor played the majority of his games at second one last time in 1990 before shifting into a DH who occasionally played first base. In 1991 he led the league in three counting stats — runs, hits, and triples. How many times has a primary DH led their league in triples, I wonder? That season was also the second time Molitor lead the AL in plate appearances and at bats. In fact, Molitor was finally healthy enough that he strung three 700+ PA/ ≥140 OPS+ seasons together in his ages 34–36 seasons.

The last of those was his first season in Toronto, where he wore Nº 19 to honor his former double play partner, Yount. Rate-wise, his .332/.402/.509 line was second only to his 1987 performance (.353/.438/.566), but it came in 160 games instead of 118. His 22 homers were a career high. Toronto repeated as World Series champs, and Molitor was named the World Series MVP. He finished second in the AL MVP voting, the highest of his career. His batting line was even better in 1994; when the strike ended the season, Molitor was hitting .341/.410/.518 (138 OPS+). He slumped to a 101 OPS+ in his last year north of the border. At 38, with a thick medical chart, and with 211 hits between him and 3000, one might have wondered if he was heading for a curtain call in 1996.

Which, finally, brings Molitor back to Minnesota. It was exciting to have him join the Twins, who looked to have Chuck Knoblauch hitting ahead of Molitor, Kirby Puckett , and 1995 Rookie of the Year Marty Cordova. The Twins had a young pitcher from Eau Claire named Brad Radke heading into his second season, and Rick Aguilera was going to try to return to starting after six seasons as a closer. Frankie Rodriguez, Rich Becker, Eddie Guardado, Mike Trombley, and prospects Matt Lawton, Todd Walker, and LaTroy Hawkins offered some excitement or hope, respectively, but it was a tough time to root for the Twins. Dave Winfield's 3000th hit in 1993 should have been a still-fresh memory, but it must have felt a longer time ago to many Twins fans. Given Kent Hrbek's retirement, the strike, and the sudden loss of a franchise icon with Kirby's glaucoma diagnosis, Molitor's pursuit of his own milestone was the best thing the Twins had going in 1996.

He didn't disappoint.

I'm not sure how many people expected Molitor to reach 3000 hits in 1996, but it would have been a tall order for any 39 year old. He didn't shrink from it, playing 161 games with 71. The last day his average was below .300 was heading into the fourth game of the season. Somehow, his third lowest average, .318, came on 22 July. From that point on, Molitor hit .378/.426/.524, with 19 doubles and 6 triples. His BAbip was .412. The hits just kept coming. He finished the year with 41 doubles, at the time one of just three players to hit at least 40 at age 39 or later. (The other two were Tris Speaker & Pete Rose. Craig Biggio & David Ortiz have since joined them.) The last of those triples was this one:

There's so much to love about this video. The triple, obviously, and the fact that he wasn't thrown out trying to stretch the hit further than it wanted to go. Molitor's expression after standing up from his slide. TK's appearance, as Dick Bremer notes, was rare enough considering his preference to let players celebrate their accomplishments without him, but to top it off, TK's wearing a snap-back hat for some reason. The Kaufmann Stadium crew play a montage of Molitor's career highlights over The Boss' "Born to Run," which hits you a little different at 39 than at 21. Robin Yount is watching from a suite, wearing one heck of a mustache, and Linda Molitor's hair is every bit as epic. The tape artifact just after the three minute mark suggests we're lucky the highlight even survives, as does the MSC logo in the upper right.

Molitor played two more years for the Twins. He was still above average at 40, with a 104 OPS+. At 41, it was clear he'd reached the end of the line as a player, and the team was also heading into a period of transition. Knoblauch was traded after the '97 season, and the pieces of the team that rallied back from the brink of contraction were only starting to fall into place. Matt Lawton and David Ortiz had found spots in the lineup, and Corey Koskie and Torii Hunter got their first tastes of major league action. On the pitching side, Radke, Guardado, Hawkins, and Eric Milton were all active, though Milton was a rookie and Hawkins hadn't yet moved into the bullpen. Rick Aguilera was in his last full season with the Twins. Terry Steinbach had one year left of his own personal homecoming. Marty Cordova was a year from free agency. Todd Walker hadn't yet worn out his welcome.

More significantly, Tom Kelly was nearing retirement. Two World Series victories were highs for any manager would probably endure considerable hardship, but the years between them hadn't been easy, and the years since the Twins' last winning season in 1992 must've compounded the toll. Molitor was there for the last two, serving as TK's bench coach in 2000 and 2001. TK got the Twins back to a winning record in his last year, then resigned. Molitor and Ron Gardenhire were immediately named by sportswriters as potential successors. As the contraction attempt unfolded, Molitor removed his name from consideration in early December. Gardenhire got the job, Seligula's contraction attempt was thwarted, and the Twins began a run of regular season success and postseason futility that is still hard to think about.

Molitor took the hitting coach gig in Seattle in 2003, but returned to the Twins as a roving minor league instructor. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2004, wearing a Brewers cap, the second ballplayer from St. Paul to reach Cooperstown. (Hopefully another guy from St. Paul will join him in a few years.) Molitor finally joined Gardy's staff in 2014, and the rest of his story is recent enough to not need recounting.

When he arrived in Minnesota, Molitor had reverted his uniform back to Nº 4. His SABR bio claims that, when Molitor chose that number in Milwaukee, it was in part due to his admiration of Bob Allison when he was a young Twins fan. That's a neat baseball story, if it's true, and it's fair to say he wore it well.

Augie Ojeda

For some reason, the Twins issued Nº 4 to Augie Ojeda in 2004.

When discussing your favorite sports teams, how should you refer to them?

- They (50%, 6 Votes)

- Don't care (33%, 4 Votes)

- We (17%, 2 Votes)

Total Voters: 12